笔者按:2010年春季学期,笔者担任了Deni Ruggeri博士的助教。与传统的设计课不同,在这门毕业设计课里,学生们不再局限于画分析、做设计,而是担当起项目的领导者,与客户洽谈,发起社区会议、问卷调查,与客户、外来专家共同商议项目的未来。老师的角色从“领衔主演”转而“退居幕后”,将闪光灯留给了学生。一个学期下来,学生们为即将步入的执业阶段做足了准备。笔者在该课程结束后访问了Ruggeri 博士,与他就这门设计课做了更深入的交流。

Dr. Deni Ruggeri

采访对象:Dr. Deni Ruggeri(以下简称Ruggeri)

采访者: 钟惠城(以下简称钟)

采访时间:2010-06-13

钟:作为您的助教,我经历了该毕业设计课(capstone studio)的全过程。一个学期走下来,我们发现这样的毕业设计课有别于传统的设计课(design studio),这样的实践与体验为我们从学业向将来执业的过渡提供了极好的机会。这便是我想和您聊聊这一话题的原因。首先,您能否简单地谈谈该课程的形式和灵感来源?

Ruggeri: 这门课的灵感来源于我对传统设计课构建形式的不满意,以及对“教与学”的关系凌驾于多方对话之上的不满意。因为beaux-arts 传统的影响,风景园林师接受的是一种线性的、“分析/综合”模式的教育,这样的教育以个人直觉以及老师与学生的互动为中心。

这样的个人主义途径是有问题的,并且与风景园林这种需要通过团队合作、不断检验与斡旋才能产生解决办法的实践是相冲突的。多年以前,当我首次有了搭建一个新设计课形式的想法时,我研究了哈佛大学设计研究生院Carl Steinitz的实践。Steinitz发展了一种新的教育模式,旨在培养“指挥家”,而不是传统的“独奏者”。在这样的过程中,学生被要求扮演领导者的角色,形成对手头问题共有的一种理解,并最终达成反应整个学生团队所关注的问题的解决办法。

在设计课里,我根据自己作为一名社区设计师的经验,通过团队活动以及其他形式的团队合作扩展了Steinitz“指挥家”的模式。这其中包括“视野转换”(”visioning chairs”)练习,在这个集体活动里,学生们分享他们对场地的机遇与限制的解读;还有目标设定练习,即学生们基于对场地未来的共同理解而发展出来的项目目标。

观点的分享与对话的机会贯穿于设计课的始终。学生有机会在该课程的风景园林学习中培养自身的能力,或利用学生之前的专业背景,作为更大群体的顾问(笔者注:在美国,三年制的MLA为非风景园林背景的学生而设,因此拥有其他专业背景的学生可以作为其他人的顾问)。每周的研讨班(seminars)让每一位学生向他们的同伴就相关话题做专题讲座。同时,设计课为对等评论(peer-to-peer reviews)提供了各种机会,学生们相互提出建设性的评论并推动整个项目往前运作。

最后一个环节,便是该设计课圈子之外的团队协作。毕业设计课的学生与社区成员、其他研究机构的同龄人一起工作,并从世界各地学术机构的教员评论中获益。为此,信息技术拓展了教室的视觉空间。这种维系全球范围内不同参与者的挑战,是推动风景园林学生拥有跨文化视角的关键。

图1:并肩作战,卡塔尼亚大学与康奈尔大学的学生同在一项目Photo credit: Deni Ruggeri

图2:项目汇报,远程科技派上用场Photo credit: Huicheng Zhong

钟:这门设计课融合了多种能力的培养与实践,如:分析、展望、领导、设计与表达等技能。其中,领导能力的培养是我最喜欢的一部分,我总是为学生们自发组织与客户和社区成员进行的多场会议而感到惊叹。在这一方面,你的目标是什么?我们的学生做得怎样?

Ruggeri: 作为一位风景园林教育者,我觉得自己有责任让学生得到最好的职业训练,除了要给予他们成为好设计师所必须的实践知识和技能,还要有批判性思维和领导能力,这些能力是成为一位“有远见的从业者”(”enlightened practitioner”)所必须的。

为了培养他们的这些技能,我布置给他们的第一个任务便是创建一个“力量图”(”power map”),这是一个反映参与该项目的各个团体及各方利益关系的图像表达。这张力量图允许学生针对特定的使用者或者群体、被忽视群体或者是一些对于项目结果最有影响力的因素,因此能让他们更有效率地进行决策。领导能力的培养也很关键,我要求学生在不同层面上与社区和项目干系人沟通,同时在项目的不同阶段向客户与社区汇报他们的进展。通过对客户的汇报,学生被要求整合出信息,并发展出一套简洁、高效的沟通框架。最特别的是,学生/领袖们成为该项目的代言人,教师的角色在整个过程中转换为导师和项目过程的“提速者”(”expeditor”)。

图3:学生们正在讨论并制定“力量图”,2010年春季毕业设计课Photo credit: Deni Ruggeri

钟:除了领导能力的培养,大量的会议、问卷调查和调研揭示了设计课的另一个关注点:社区参与。很多注意力被放在了社区参与上,这是因为项目本身的性质、教师或学生的兴趣所在、或者是其他原因?学生们在进行社区互动时有遇到什么困难吗?如果有,您如何指导他们应付这些问题?

Ruggeri: 作为一位社区设计师,我坚定地认为我们必须倾听那些每天都生活在将要被设计的土地上的人们的声音。不管设计师访问了场地多少遍,不管他的分析技能有多熟稔,设计师也无法获得对这片土地独特性的最深刻和最真实的理解。通过倾听社区的声音,我们可以尽可能地接近“局内人”的视角和对问题真实的理解。

图4:意大利卡塔尼亚当地社区,学生走访中Photo credit: Huicheng Zhong

当然,社区参与有着它自己的挑战,设计课里的学生很快便意识到了它们。首先,其中一个挑战是决定什么时候需要社区参与什么时候不需要,以及设计师是否需要考虑所有的社区需要和意见。关于这个问题,这里没有一个“万能”的解决办法。然而,在项目不断展开的过程中,我鼓励学生随着我们理解的变化多次倾听社区的反馈。此外,我们需要多元化的方法让社区意见出现。在研究中,这种方法叫“三角原理”(”triangulation”),比方说利用不同的办法(定量、定性,或两者结合)来回答相同的问题。通过比较与对比结果,学生们可以整合出一个“更大的蓝图”,或者是“完全形态”(”gestalt”),而不仅仅只是所有意见的堆叠。

时间是任何设计项目的敌人,尤其在这样一个把社区参与作为主要原则的设计课。除了时空上的限制,我发现所有学生都能令人满意地投入到社区参与中去。科技帮了我们一把。在线与邮寄形式的问卷调查、拦截访问调查、分组座谈会(focus groups)、电话会议、Skype等,这些是学生们在设计中用于社区参与所使用的一些方法。在这一学期的毕业设计课里,我们用问卷的形式调查了五百多名居民、进行了数十小时的分组座谈活动、社区作坊和汇报,所有这些都没有影响设计的质量。事实上,我见证了他们因此而更强有力、更贴近主题的设计作品。

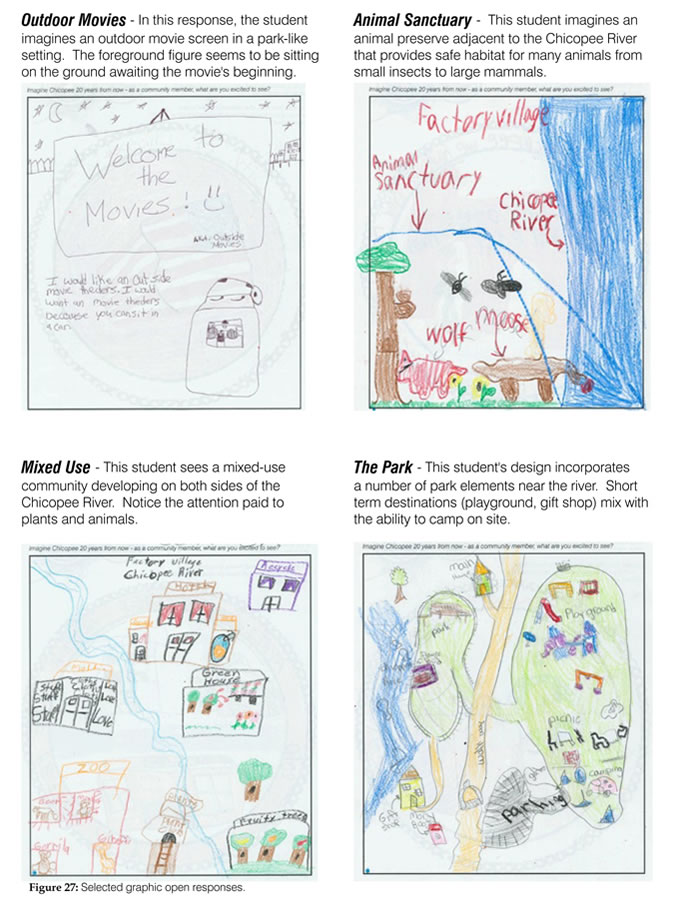

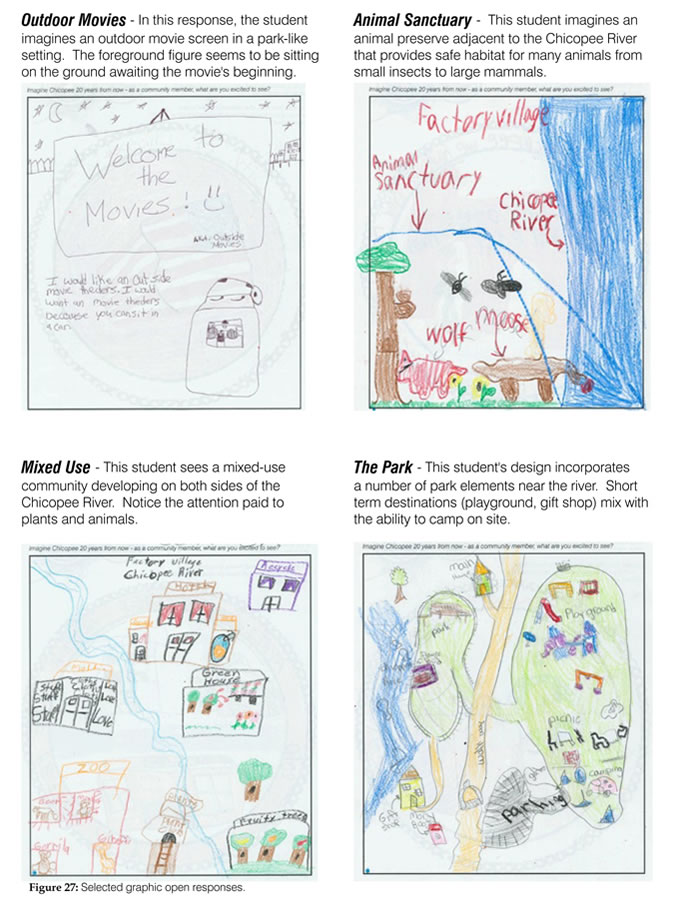

图5:涂鸦, 社区孩子们对一份问卷调查的反馈Photo Credit: the Chicopee Team, spring 2010 studio, Cornell University

图6:另一项问卷调查的数据分析Photo Credit: the Chicopee Team, spring 2010 studio, Cornell University

钟:您使用 “指挥家”与“提速者”来形容学生和老师,在这门设计课里,您是如何看待老师作为一个“提速者”的角色的?你的目标实现了吗?最大的挑战又是什么?

Ruggeri: 正如我所说,我借用了Steinitz的教育方法。然而,我调整了他的模式让其适应我们所做项目的独特性和我个人的技能和专长。

作为提速者,我的主要角色是为设计课的运作与成功提供框架,一个既理论又实际的框架。这个框架包括一个勾勒目标的教学大纲(通常是长达数页的内容),实验性的阶段和最终成果。作为提速者,我也负责搭建与客户的初始对话并把项目推销给学生。作为提速者,我的角色还要确保学生们的学习轨迹是积极的。这需要引导学生做一些特定的阅读,提供学生们可以利用的外部资源,搭配在技能和兴趣上互补的学生。其中最重要的任务是评价每一位学生的能力,以及组织一支让每位学生都发挥所擅长能力的队伍。

我所面临的这种类型的设计课的挑战,其中一个与“著作权属”有关。在传统的设计课里,教师可以在最终成果的著作权属中声称其主要的角色,但这类设计课并不允许教师扮演“领衔主演”的角色,反而是“退居幕后”,把闪光灯留给学生们。

图7:汇报成果Photo credit: Huicheng Zhong

另一个与传统设计课教学不同的是,提速者需要依赖外来专家。在传统设计课里,教师熟知场地的一切,掌管着这些信息的钥匙。基于这门团队合作的毕业设计课所选择的场地的复杂性,我必须求助外来顾问、评论家和同行教员的帮助。尽管学术界经常提倡“独立”作业并将自我表达和自我推销凌驾于跨学科与团队协作之上,这是完全可以接受的,同时这也是与风景园林实践相一致的。

钟:Ruggeri博士,非常感谢您接受风景园林新青年的访问!

An Experiment on new models of capstone studio – Interview with Dr. Ruggeri

In the spring semester of 2010, I was the TA of Dr. Ruggeri in his capstone studio. Different with traditional studios, students were no more confined to drawing analyses and doing designs in this capstone studio, but played as leaders, meeting with clients, setting community conferences on their own, and visioning projects’ future collaboratively. The instructor stepped back from the role of “prima donna”, leaving the spot light to the students. After the course I interviewed Dr. Ruggeri and further communicated with him about this capstone studio.

Dr. Deni Ruggeri

Zhong: As your teaching assistant, I experienced the whole process of this capstone studio. The outcome of it turned out to be different from the traditional design studio, which provided great opportunities to transition to our future professional practice through real-time projects. This is the reason why I am interested in talking/interviewing with you on this topic. So firstly can you briefly talk about its inspiration and format?

Ruggeri: The inspiration for the “collaborative” capstone studio came from my dissatisfaction with the way studios are normally structured, and with the privileging of the instructor/student relationship over the dialogue across the various participants. Because of the legacy of the beaux-arts tradition, landscape architects are trained according to a linear, “analysis/synthesis” model (Ledewitz) focused on personal intuition and on the interaction between instructor and student.

This individualistic approach has been problematic, and is in conflict with Landscape Architectural practice, where the best solutions come from a collaborative process of constant testing and negotiating of ideas and perspectives. Years ago, when I first became interested in developing a new studio format, I researched the work of Carl Steinitz, professor at Harvard’s University Graduate School of Design. Steinitz developed a pedagogical model based on a new paradigm whose goal is to train what he calls “conductors”, rather than the more traditional role as “soloists.” In his process, students were asked to take on leadership roles, develop a shared understanding of the problems at hand and ultimately come to an agreed upon solution that would express the concerns of the entirety of the student body.

In my studios, I have expanded on Steinitz “conductors” model by introducing group activities and other forms of collaborative exercises borrowed from my experience as a community designer. These include the “visioning chairs” exercise, a group activity during which students share their findings and opinions about the studio site and its constraints and opportunities, and goals setting and visioning exercises, during which students develop as a class series of project goals based on their shared understanding of the site’s future.

The sharing of ideas and opportunities for dialogue are built into the entire structure of the studio. In particular, students have the opportunity to build on skills they may have developed over the course of their landscape architecture studies, or during their prior careers and act as consultants to the larger group. Weekly seminars allow each student to give fellow classmates talks on specific topics relevant to the topics covered by the studio. The studio also offers multiple opportunities for peer-to-peer reviews, during which studio participants can constructively critique one another and help move the work of their classmates forward.

One last component of the collaborative studio has been the extending of the collaboration beyond the walls of the studio. In more than one case, students in the capstone studio have worked with community members, students at peer institutions, and have benefited from critiques by faculty at institutions in various parts of the world. In order to allow this, information technologies have been used to expand the classroom into virtual space. As challenging as organizing a studio involving multiple actors across the globe might be, this is key to promote in landscape architecture students a cross-cultural perspective.

Fig. 1 Students from the University of Catania and Cornell University work collaboratively on a visions for the landscape of the modernist new town of Librino in ItalyPhoto credit: Deni Ruggeri

Fig. 2 Students presenting their projects using long-distance technologyPhoto credit: Huicheng Zhong

Zhong: This studio involves a wide range of skills learning and practices, such as analytical, visioning, leadership, design and representation skills. Among them leadership building is my favorite part, I have always been amazed by those conferences organized by the students with different clients and parties. What was your goal in this spectrum and how did everyone do?

Ruggeri: As an educator in Landscape Architecture, I feel the responsibility to train students to be the best they can be, both in terms of giving them both the practical knowledge and skills necessary to become good designers, as well as the critical thinking and leadership skills needed to become what I called “enlightened practitioner.”

In order to build these skills, I ask students as one of their first assignments to develop a “power map,” a graphic representation of the various actors with a stake in the project we are working on and the relationship between and across each actor. This power map allows students to affect the decision making process more effectively, or to target specific users and user groups, underserved populations, or the actors with the most influence on the final outcome of the studio. Also critical to the development of leadership skills is the requirement that students engage with communities and stakeholders at multiple levels, and that work is presented to clients and communities at various stages of the process. By having to present to clients, students are forced to synthesize the information and develop a communication framework that is clean, concise, and effective. Most of all, the student/leader becomes the spokesperson for the project, leaving the instructor the role of mentor and “expeditor” of the process.

Fig. 3 Students in the Spring 2010 collaborative capstone studio brainstorm a “power map” of their projectPhoto credit: Deni Ruggeri

Zhong: Besides leadership building, those conferences and surveys disclose another focus of the studio: community involvement. A lot of attentions were given to community participation, is that because of the nature of the projects or the instructor’s/students’ interest or any other reasons? Are there any difficulties for the students in involving community participations? If yes, how did you advise/guide them in handling these problems?

Ruggeri: As a community designer, I am a firm believer in the need to listen to the voices of those who live their daily lives in the places we are called to design. No matter how many times one visits the site, or how sophisticated one’s analytical skills are, no designer can gain a deep and authentic understanding of the uniqueness of a place. Through listening to the community we can get as close as possible to the “insiders’” perspective and to the true understanding of the problems we are asked to solve.

Fig. 4 Students visiting a neighborhood in Catania, ItalyPhoto credit: Huicheng Zhong

Of course, community participation has its own challenges, and students in my studio quickly become aware of them. First and foremost, one of the challenges is to decide when community input is necessary and when it isn’t, and whether the designer should address the opinions and needs of the community in full or not. There is no “one size fits all” solution to the question. However, I encourage students to visit the community feedback at multiple times during the course of the studio, as our understanding of the worlds may change and become more nuanced as the process unfolds. Moreover, we need to develop multiple methods to allow community opinions to emerge. In research, this is called “triangulation,” i.e. the use of multiple methods (quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both) in order to answer the same questions. By comparing and contrasting findings, the students should be able to synthesize a “bigger picture,” or what I called a “gestalt” that is more than the sum of all the voices heard.

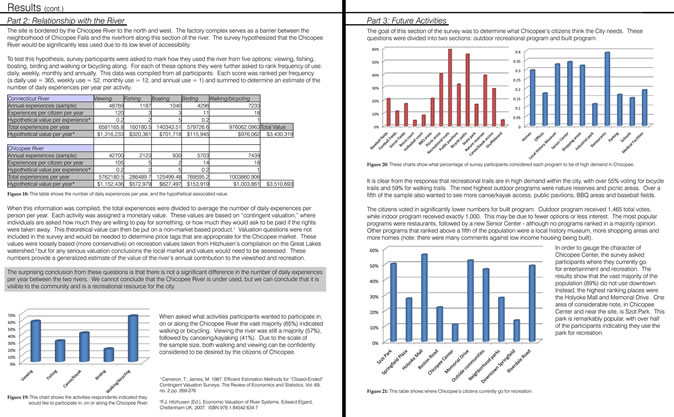

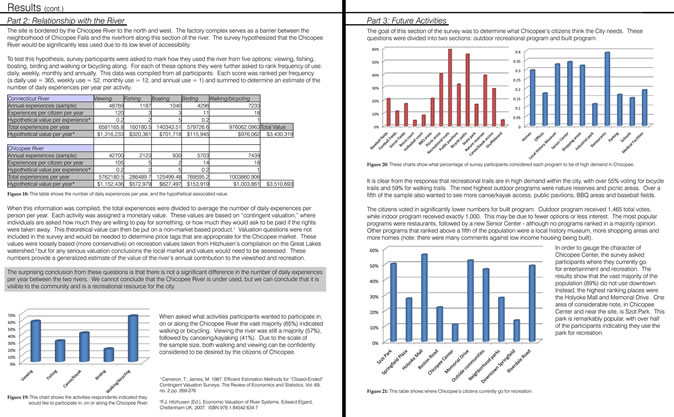

Time is of course the enemy of any studio project, but it is particularly so in the case of studios where community engagement is a key principle. I have found that despite the geographical and temporal limitations, all of my students have been able to gather community input in a more than satisfactory way. Technology has come to our rescue. Online and mail-in surveys, intercept surveys and interviews, focus groups, observations conference calling, skype are only a few of the methods students have embraced in trying to engage communities in the design process. My latest capstone studio involved more than 500 residents surveys, hours of focus group activities, community workshops and presentations, all of whom have occurred without sacrificing the quality of the work. In fact, the work I have witnessed has been stronger and more relevant than ever.

Fig. 5 Graphic responses to the surveyPhoto Credit: the Chicopee Team, spring 2010 studio, Cornell University

Fig. 6 Analyses and results from another surveyPhoto Credit: the Chicopee Team, spring 2010 studio, Cornell University

Zhong: You used the terms “conductors” and “expeditor” describing students and instructor. How did you perceive your role as an expeditor during the course of studio? Was your goal achieved? What was the biggest challenge?

Ruggeri: As I mentioned, I borrowed the terms from Steinitz’s pedagogy, however, I have adapted his model to fit the uniqueness of the projects I have worked on as well as my own skills and expertise.

As expeditor, my primary role has been to provide the framework, both theoretical and practical, for the functioning and success of the studio. This consisted in a syllabus (often many pages in length) outlining the goals, tentative phases, and ultimate end product. As expeditor, I have also been in charge of developing the initial dialogue with the client and market the project to the students. As expeditor, my role has also been that making sure that each student’s learning curve is a positive one. This requires directing students to specific readings, offering suggestions with regard to outside sources of knowledge they may be able to tap into, pairing students that may be complementary in their skills and interests. One of the most important tasks has been that of assessing the abilities of each student and trying to create teams that would foster each student’s development in terms of his or her abilities.

One of the natural challenges I have faced in this type of studio is related to “authorship.” While in traditional studios the instructor can claim a major role in the authorship of the final products, the collaborative studio does not allow the instructor to play the “prima donna” role, relegating him to a “behind the scene” role, leaving the spot light to the students themselves.

Fig. 7 Students presenting their community participation productsPhoto credit: Huicheng Zhong

Another way in which the expeditor role has differed from traditional studio instructorship has been the necessary reliance on outside experts. In traditional studio, the instructor becomes he who knows the site inside out, and holds the key to this knowledge. Given the complexity of the studio sites chosen for the collaborative capstone studios, I necessarily had to tap into expert knowledge through the involvement of outside consultants, critics, or fellow faculty members. This is perfectly acceptable and consistent with the way landscape architecture is practiced in the real world, yet it does raise issues, as academics are often judged and evaluated for their “independent” work, privileging self-expression and self-promotion over collaboration and multi-disciplinarity.

Zhong: Dr. Ruggeri, thank you so much for accepting our interview.

- Dr. Deni Ruggeri is currently assistant professor of Landscape Architecture at Cornell University. In the fall of 2010 he will assume the new position of Assistant Professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Oregon.

- Dr. Ruggeri is trained as an architect, landscape architect and urban designer. He holds a Ph.D. in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning from the University of California, Berkeley, Masters of Landscape Architecture and City and Regional Planning from Cornell University, and a Laurea in Architettura from School of Architecture of Milan’s Polytechnic in Italy.

- Dr. Ruggeri’s research focuses on the interface between physical environment and human behavior. His research investigates the influence that urban design and landscape architecture have on people’s place identity and attachment to everyday neighborhood landscapes. Additional research interests include social factors in urban design, and the investigation of the role that landscape architecture has played in the planning and design of European and American new towns. He is the co-editor of a spring, 2007 issue of the Journal “Places,” and the author of various articles published in books, academic journals and conference proceedings.

- In addition to research, Dr. Ruggeri has practiced landscape architecture and community design, working on urban design, park design, streetscape and land planning projects for the SWA Group and Design Workshop, Inc. His most recent projects include the master planning, design and construction of the Jeffrey Open Space Trail in Irvine, CA, the residential communities of Ridgegate in Colorado and Spanish Walk in Palm Desert, CA and a new town center for Westport, California.

- Dr. Ruggeri is currently working on a grant funded by the Department of Agriculture entitled “From Rust to Green in NY State,” whose goal is to promote a shift in the narratives of many rustbelt cities from economic depression and job loss to sustainable development and green infrastructure. Other research projects include a series of post occupancy evaluations of new towns and master planned communities worldwide, including the garden city of Harlow, England, Mission Viejo, California and the new town of Zingonia, in Italy, and the creation of a new park system linking small archaeological sites in the Naples, Italy metropolitan area. Over the past few years, Dr. Ruggeri has been engaged in developing a new model for landscape architecture studio education based on collaboration, peer teaching, and the use of new information technologies. Samples of student work from the virtual/collaborative capstone studio can be found at: http://www.landarchy.org/studioLibrino/

非常非常不错啊~~~ 好像这种社区真实项目的STUDIO在景观教学里挺流行的吖。我听的好多同学都有这种设计课。 谢谢CITY介绍~!

“这类设计课并不允许教师扮演“领衔主演”的角色,反而是“退居幕后”,把闪光灯留给学生们。”

——————称职的老师!

文章很好,仔细研究了好几遍,可能由于没有亲身经历的原因,一些关键内容不得其解。

能否进一步介绍?对国内教育更有帮助。

1、毕业设计如何选题?是虚拟课题还是现实课题?——谁来扮演客户、社区、外来专家?如果是真实身份,如何组织客户、社区和学生的关系?在国内,实际项目一般很难接纳学生的工作,社区和客户要求看到专业的设计师工作,很不喜欢看到一群学生来见习。

2、如何引导学生在规定时间内达成预定目标?而不是流于空谈或者无休止的争论——在这过程中,保持学生独立性,而非走过程最终由“教师说了算”?

3、如何保证研讨结论具体落实。我们知道,一个想法落实在设计中仍然有设计技巧、工程实现等问题。这种毕业设计是倾向于概念讨论,还是具体落实。如果要落实,如何保证前一阶段理想的贯彻,要知道,有很多好的想法,由于学生在设计技巧的生涩和对工程技术的不了解,流于空谈。如果从贴的几张学生概念图上看,国外学生显然仍然存在这方面问题。

4、如何保持学生积极性?——如果偷懒长期无工作成效,甚至编造调研数据应付讨论,是否有这样的学生?有何激励机制?

5、能否贴最后的成果看看?

呵呵,多谢阿

@王欣, 很赞同你的想法,也很想倾听作者的观点!

@王欣, 抱歉这么晚才回复!王老师的问题都十分就事论事,要回答就得展开很长的故事背景,若您不介意,我想跳出来说说自己的观点。

我觉得,首先,老师不应该去建立什么模式,而应该采用自己特有的教授方法。每个老师都有自己的专长、兴趣、性格和关系网,根据这些组织自己的授课方式是最好的。每个老师都有激励自己学生的办法。

以此课程为例,该模式也是因为老师的背景而产生的,客户和邀请来的专家都和老师本人有较好的个人关系。老师本人性格也十分外向、善于沟通并愿意主动沟通,于是,他就尽最大能力把关系铺垫好、把推动工作做好。

其次,这里有一个前提,这样的课程只适合毕业生,而且是硕士毕业生,此时的他们已经具备了相当的设计能力,尚待磨练/检验的是他们驾驭一个项目的能力和沟通、表达能力。

在这样的前提下,延伸出来的问题是:老师的教学目的到底是以学生们的成长为动力还是以成果的质量为动力呢?

这篇文章给我挺多启发的,最近在思考做设计的logic way,发现原来没有。有许多方式都可以达到最后的结果。在真实环境中赋予责任给学生,这样学习效果会更好,而且这门课让人学到的东西很实用。

以学生的观点来看,我觉得让学生模拟从业者与业主直接对话确实很锻炼人,但是这得依赖学生的自觉性,如果学生还是没有转变角色,只当游戏来做呢?怎么引导学生用专业的态度来对待整个项目呢?