编者按: 天津桥园项目以全面改善生态系统服务为目的,依赖自然进程修复污染的土壤并处理城市雨水。今天,桥园公园成为了具有雨洪蓄留、乡土生物多样性保护、环境教育与审美启智和提供游憩服务的、多功能生态型公园。

In the Chinese city of Tianjin, the strategy of “adaptive palettes” was used to create a series of biologically diverse ecosystems that could repair contaminated soils and treat urban stormwater by relying on nature’s processes. Today, Qiaoyuan Park has reclaimed a brownfield by integrating regenerative ecological functions, using native plants in a landscape that is allowed to adapt and evolve, and educates visitors in a relaxing recreational space designed for the dense community surrounding the park.

声明:此文为正式授权文章,已征得作者同意在风景园林新青年(Youth Landscape Architecture)上发表,不得转载,需要授权转载发布者,请联系作者或TOPOS杂志(www.topos.de)。

Notice: This article is a reprinted version with the official permission of the author. Do not copy without permission.

Article Source: Kongjian, Yu. Qiaoyuan Park, An Ecosystem Services- Oriented Regenerative Design. TOPOS, VOL. 70. June, 2010.

1.Introduction

China’s rapid economic growth and urbanization often raises questions about the sustainability of projects that seem to go up overnight (Shannon, 2009). In a country where space is at a premium, open space in urban environments is typically subsumed to make room for the influx of residents. The lack of readily available resources combined with rapid urbanization gives rise to more sensitive environmental approaches and China is well-positioned to lead the way for responsible sustainable urban development and restoration.

Figure1: The site plan (also showing the positions where the photographs are taken)

Green space has historically been an asset because of the psychological and physical benefits to the surrounding community. The reality of many traditional urban parks, however, particularly those built within the last 20 years, is the economic and environmental burden they present to the city through maintenance, repairs, and water and energy consumption. While the beauty of traditional ornamental parks has been appreciated, the more authentic and vigorous “beauty of wild grass”(Yu, 2006, 2009; Yu and Padua,2007) of vernacular landscapes is undervalued, especially in terms of the sustainable services they provide. Storm water management, including minor flooding, is often seen as a threat to urban progress. Slow moving streams and rivers were straightened and channelized to move water efficiently, resulting in the loss of groundwater supplies and the availability of potable water around the world. Native plants have been replaced with mass swaths of ornamentals that lack biodiversity. Taming nature’s messy ecosystems into more sophisticated urban parks has all but removed nature’s ecological benefits.

Figure2: The existing conditions of the site: a former shooting range, shown as a garbage dump and drainage sink for urban storm water, heavy polluted with saline-alkali soil, littered, deserted, and surrounded with slums and rickety temporary structures.

2. Ecosystem Services Oriented Design

As engineering and mechanized services have been standardized throughout the urban world, natural systems have been severely degraded or completely destroyed. When an ecosystem is no longer sustainable, it is forced to rely on human control for services such as water and wastewater treatment, food production, habitat protection, and rehabilitation. When the ecosystems are damaged, the environment becomes sterile, blighted and/or contaminated and requires human intervention to repair it. We often find ourselves approaching the problem with nearly the same solution that caused it. We create new public spaces with neatly placed shrubs and treat contaminated water and soils using mechanical methods, and celebrate a restored environment. The contamination is addressed but at a significant expense to the government or people, and the environment is still incapable of self-sustenance.

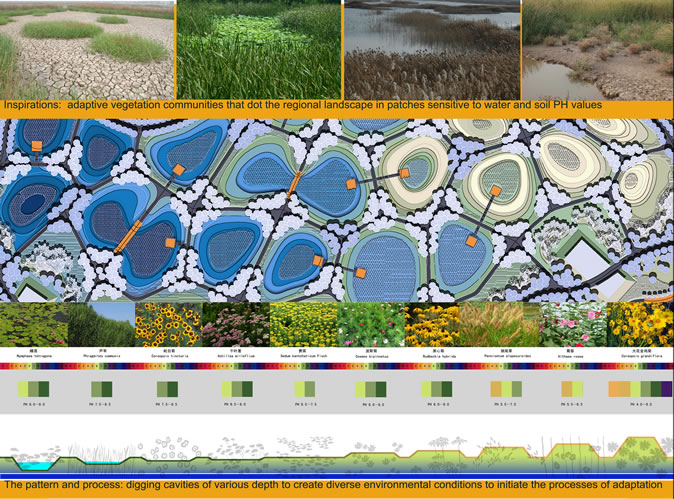

Figure3: The design concept: let nature work: the adaptation process visualized in habitat patches sensitive to water and soil PH values. It was inspired by the regional landscape with patchy habitats sensitive to subtle changes of water and PH values

It is therefore critical to recover landscape as a living ecosystem that has the ability to adapt, change, and providing ecosystems’ services including: Provisioning services (including food, water and energy) ; Regulating services (such as purification of water, carbon sequestration and climate regulation, waste decomposition and detoxification, crop pollination , pest and disease control); Supporting services (such as nutrient dispersal and cycling, seed dispersal and Primary production); and cultural services (including cultural, intellectual and spiritual inspiration, recreational experiences, ecotourism and scientific discovery) (Constanza and Daily,1992; Constanza, et al. 1997; Daily 1997, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) , 2005). The Qioyuan Park in China’s Tianjin City showcases the ecosystem services-oriented approach to landscape restoration in the middle of a densely populated urban setting.

Figure4: The bird-eye view of the park from the south-west corner showing the divers patchy landscape of pond cavities occupied by various plant communities (Summer)

Figure5: The bird-eye view of the park from the south-west corner showing the divers patchy landscape of pond cavities occupied by various plant communities (Fall)

3. Site: The Qiaoyuan Park

The adaptive palettes of Qiaoyuan Park is a experimental showcase of regenerative design. The redevelopment strategy integrates site topography, groundwater table and native habitat to inspire a design that will rejuvenate nature’s ecosystem services. The project reactivates valuable open space and rebuilds a diverse native habitat that will be able to manage storm water, infiltrate groundwater, and educate the community about the beauty of the native landscape.

The site is located in the Hedong district in one of the largest and oldest districts in Tianjin, China with a surrounding community population of 300,000. The 22-hectare site is an abandoned shooting range, transformed into an illegal dump after years of neglect, where storm water from urban runoff draining to the site contaminated the soil and water. Only a few poplar and willow trees had survived and adjusted to the saline and alkaline soil. An informal community was living on the edge of the site but the community was relocated and the buildings were demolished prior to design consultation.

Figure6: A deep water ponds in the Fall

Figure7: A deep water pond occupied by water lily in the water and surrounded on the shore by Rosemallow (Hibiscus syriacus) and Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) and many others (Summer)

The park is named Qiaoyuan – ‘qiao’ meaning bridge and ‘yuan’ meaning garden – The Bridgepark. The name is derived from one of the few remaining expanses of open space in the area and its location adjacent to the Weiguo highway interchange. The southern and eastern face the community ensuring a strong connection to the neighborhood in the future.

4. Strategy: Regenerative design

The regeneration of Qiaoyuan Park is part of an environmental improvement program supported by city leaders to initiate environmental restoration using more sensitive environmental approaches. The intent was to build a park that was able to manage urban storm water, rehabilitate and preserve biodiversity, restore and preserve the vernacular landscape, and provide recreation for adjacent communities. The design strategy is simple – let nature perform the role of ecosystem restoration. The approach veered away from conventional solutions and focused on ecologically sensitive design so the park would become an investment for the city as a low-maintenance high-performance landscape.

5. Analysis: Ecological restrictions and opportunities

Tianjin is located in the lower piedmont alluvial plain of Haihe River, near the estuary of the Bohai Gulf. The shallow groundwater table and slight changes in topography translate into highly varied soil properties, allowing a variety of plant communities to thrive. Decades of development has destroyed the coastal plain landscape once rich with wetlands and salt marshes. This flat and subtle native landscape inspires the restoration of the degraded landscape in the city. As one of the oldest districts in Tianjin, the landscape is highly fragmented and polluted,. The proposed redevelopment of the coastal wetland landscape has the capability, once again, of performing important ecological roles related to water and habitat management.

Figure8: A deep water ponds in the Fall

Figure9: A deep water ponds in the Winter

The location adjacent to a major highway and existing topography inspired the water management strategy for the park. The low site elevation and shallow groundwater table creates a myriad of ecosystems that will evolve and adapt depending on the variations in elevation, pH, and moisture.

6. Design: The adaptive palettes

The ecological functions of the site had been destroyed and the measure of a successful park was the integration of the ecosystems services of provisioning services, regulating services, supporting services and cultural services into the design. The challenge was to rejuvenate ecological processes using the vernacular landscape, to mitigate soil and water contamination, and allow the site to adapt and evolve naturally. The community need for an aesthetically pleasing open space for neighborhood recreation was also crucial to design implementation.

Figure10: Shallow and seasonal ponds occupaid by diverse native plant communities

(a) The creation of habitats: The first step was to regrade the site to create ponds with various depths for storm water collection, storage, and treatment. Inert onsite waste reclaimed as fill material to create topography. 21 ponds were created with each pond varies between 20-40 meters in diameter and varies in depth. The relative moisture levels and pH of each pond create micro habitats ranging from wetlands to wet prairies and grasslands.

Figure11: One of the shallow water pond surrounded by reeds at the edge creating a quite space in the middle

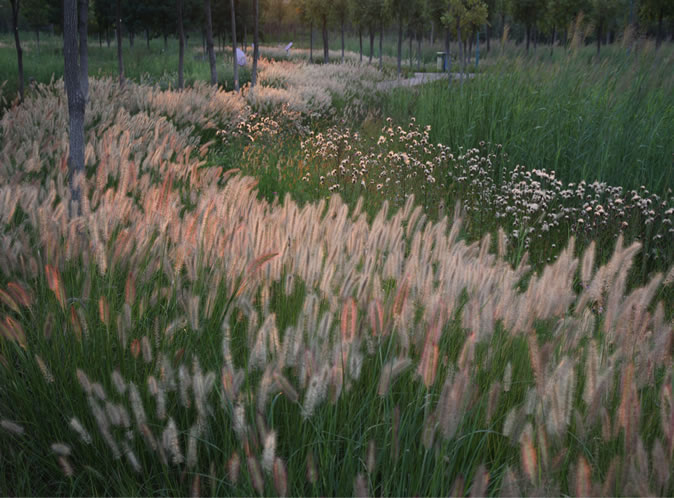

(b) Plant community design: The plant community began from seed. The seed mixes were specifically developed for each habitat so a biologically diverse plant community would flourish. The dynamic, self-evolving, and adaptive nature of the design allow species to move and change over time instead of maintaining a strict planting design. Indigenous species are encouraged to become a part of the landscape through wind and bird dispersion. The plant communities will go through several stages of succession as the site remediates and balances the saline-alkaline soil. By allowing the plant community to change throughout the year, the cycling of plants and nutrients begin a natural cycle of growth, pollination, reproduction, and decomposition.

Figure12: The autumn color of a shallow water pond showing the beauty of the “messy nature” being appreciated by visitors of various age

(c) Cultural services. The adaptive palettes is the living system and the footpaths create a network of linkages for the visitor. Willow woodlands nestle the ponds and platforms and bridges are subtly designed to submerge the visitor in an aesthetically pleasing landscape of native grasses and wildflowers. Interpretive signage of each plant community is posted at each pond to explain natural processes including the water cycle, ecological benefits, and major plant species. The park becomes a recreational space and instills a sense of stewardship and ownership for the community.

Figure13: A dry cavity upon a mound above a garbage dump. Occupied by the Aizoon Stonecrop (Sedum aizoon), and surrounded by Garden cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus) and others on the edge, totally different plant community from the water ponds and wet bubbles

7. Conclusion: Lessons

This design was initiated in spring 2006 and construction was completed in May 2008. During the first week of opening, nearly 200,000 tourists attended the opening, proving an unprecedented success. Through simple ecological regenerative design, the former unused space had become a new ecological park. Ecological services such as storm water regulating, soil and water improvement, biodiversity maintenance, stewardship, aesthetics and recreation dramatically transformed this space within two years.

Figure14: An intersection of paths where various ponds and cavities meet becomes an attraction for visitors

Figure15: The adaptive palletes; The diverse plant communities established at the edge of one of the water collting cavities with subtle variation in soil and water conditions

A powerful landscape emerged by understanding the needs of the surrounding community and employing a new environmental strategy. The regenerated ecological park has unveiled a new aesthetic in China – one that adheres to environmental ethics and a heightened sense of ecological awareness that is spreading throughout the world. This strategy reveals a bright perspective for ecological urbanism in design.

Nature’s self-recovering ability speaks strongly in this park by illustrating that engineered solutions and highly maintained spaces are not necessary for a successful regeneration program. The designers respected the vernacular landscape and its natural processes to initiate nature’s ecosystem services. Inexhaustible ecological services are gained from this approach and reveal the historic vernacular landscape to the community and the city.

Acknowledge: The author thanks Nicole Janak for her review of the article.

Design Firm: Turenscape and The Graduate School of Landscape Architecture, Peking University

Client/Owner: The Municipal Government of Tianjin,China

Photography Credit: Kongjian Yu, Cao Yang

Design Principal: Kongjian Yu

Additional Project Credits: Shi Chun, Jia Jun, Ji Sheng,Hu Hanyu, Zhang Bo, Su Xinglan, Feng Xianjun, Wang Yunfeng, Lin Li, Zhang Xuenian.

References:

Costanza, R .and H. E. Daily ,1992. Natural capital and sustainable development. Conservation Biology. (6):37-46.

Costanza, R. et. al. 15 May 1997. “The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital.” Nature 387: 253-259.

Daily,G.. C,1997. Nature’s Services: Society Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington. 155pp.

Shannon, K. (2009) ‘Can Landscape Save Asian Urbanism?’ Landscape Architecture China, October 2009, p. 39-45.

2007, Yu, Kongjian a; Mary G. Padua, China’s cosmetic cities: Urban fever and superficiality, Landscape Research, Volume 32, Issue 2 April 2007, pages 255 – 272.

2006, Yu, Kongjian, The Art of Survival: Recovering Landscape Architecture. In: Yu, Kongjian and Mary Padua (Eds.), The Art of Survival, The Images Publishing Group, Victoria, Australia, pp.10-25).

2009, Yu, Kongjian, The beautiful big feet: Toward a new landscape aesthetic. Harvard Design Magazine 31, Fall/Winter 2009/10: 48-58.

师兄不识愁滋味……

@安友丰, 唉…

全英语啊。 不过照的照片都挺好看的~~

不知道在里面走会不会觉得比较乏味,好像园子里面哪哪都差不多。

@jacklion,

that’it,对设计认同的主观性

认同它的时候,可以诠释为很“纯粹”,不被认同的时候,可以说很“乏味”,很难贴一个标签说,这是对的,那个是不对的

@程鹏, 确实不好说。我只是在想象身在其中的空间感受。“纯粹”的设计也可以提供非常丰富和舒适的空间感受,比如巴塞罗那植物园,利用非常纯粹、非常统一的设计语言依靠山地塑造了特别丰富的空间。但是这个桥园,不论从平面上看还是实景照片看,我都觉得设计做得比较平。好像设计师所有的动作都做在人的视高以下。所以这些照片里面好看的那些要么是低头拍脚下的“野草”,要么是飞起来从空中鸟瞰池塘的形状,很少有在正常视高下拍摄的照片。而且这里面有用道路分割得比较清楚的“区域”挺多,通过围合形成的“空间”却较少。或许等到这些乔木长成,能通过距离较近的树干形成很多围合比较紧密的小空间,但是这些小空间又都是交通的节点,不太可能提供很舒适的空间感受。而且对于大多数设计师来说,通常在处理水体的时候都会比较注意岸线的设计,利用水陆交界的变化塑造很多空间,但是这个设计似乎是反其道而行,用很“纯粹”的岸线形式来避免空间的多样变化。也许设计师是想在一个最纯粹的基底上最大程度地展现植物材料塑造不同空间效果的可能性,这倒也未可知。还有一个问题是,如果是生态学家规划这样的场地,一定会尽最大能力扩展湿地的面积,尽量减少道路对湿地的分割。因为将湿地切割得越碎,它能为昆虫、鱼类、鸟类等各种生物提供的栖息地就越有限,场地整体的生态效应就会越低下。但是看这个桥园,好像又在反其道而行。这种策略很可能极大地限制或破坏设计师所倚重的“nature’s self-recovering ability”。另外,所谓湿地从生态系统上讲,多是河流、湖泊、海洋等更大尺度水系的组成部分,要真正实现湿地的生态价值,需要在规划上恢复其与这些水系的空间联系和物质能量交换过程。在这个案例中,至少从发表的这些材料里,很难看出设计师在“创造”这块湿地时在这方面所做的努力。其实除了这些,我还有一个问题一直没看懂。为何要取名叫“桥园”?桥存在的合理逻辑是被水面隔离的两岸需要陆路的直接联系。但是这个园子里每个水塘都不是很大,桥其实可有可无。园中建成的”桥“连接两个水面的,比连接水面两岸的还要多。看来在建桥的逻辑上,设计师也在反其道而行。

这个项目在两年的时间内就实现了一块场地从废到兴的蜕变,深受周围居民的喜欢,从这个意义上说,确实是个很好的项目。但是叫它生态型”桥园“,我就稍微有点不明白了。

@jacklion,

因为公园毗邻高架桥,园子本身跟桥没关系,所以英文是Qiaoyuan Park,而不是bridge garden。

设计者也不是在强调空间,而是对原有盐碱地的改造。这些道路划分的区域——坑的深浅和大小是根据土壤的原有状况和雨水径流来确定的。

景观设计的途径不只有“空间营造”一种,从视觉分析的角度(空间)讲,空间的大小及变化并无好坏之分,这纯粹是一种主观判断。

@jacklion, 多谢介绍!这样多讲一讲,我们多讨论一下,相信大家对方案的理解会更好的。原来是这么个桥园,明白了。

能不能请教一下,盐碱地的改造,在这个项目里运用的是什么样土壤修复技术?用”坑“这种形式来修复是由什么样的土壤条件决定的?怎样根据雨水径流确定尺度?确定土壤的原有状况用的是什么样的调查方法?总之,能不能请您多介绍一下技术方法,以后遇到类似的环境问题,我们也好向这个项目多学习借鉴。

另外,我觉得空间是景观设计的载体,景观设计是在空间中实现的,园林本身就是空间的艺术,所以不论从哪个角度入手来进行景观设计都必须对空间进行推敲。其实尽管我个人觉得桥园的空间营造不是很充分,但它本身却也不是没有空间设计的,否则它和土壤修复的环境工程项目不就没有区别了吗?空间的大小、变化确实没有好坏之分,但是确实能给人不同的主观感受,否则桥园和凡尔赛不也就差不多一样了吗?

@jacklion,

我承认一件事情,设计师设计水准确实是有高低之分的。打一个很不合适的比方,一个人长得美还是丑是能区分出来的,不言而谕的标准,不必用科学的数据来量化,来分析研究,我们也分得出“美”和“丑”,看一眼就知道了。

除去某些“特殊的”主观审美癖好,处于同一档次的“美”给每个人的主观感受是不同的,但是我们都会承认这个东西是“美”的。

@jacklion,

忘了说另一件我也不赞成的事情,以丑为美,呵呵

@jacklion, 这个讨论特别好,我想接下去。空间一定是设计的载体,设计的过程就是推敲围合空间的过程,就是推敲植物、水、地形和其他构筑物如何围合空间的过程。空间的大小为何没有好坏之分?如果这样,那么人在棺木之中和在广阔的原野之中的感觉都是一样的吗?大小均衡的一串空间和富有节奏的大小不同的一串空间形成的设计所创造的感觉一定是不同的。生态恢复我懂的不太多,但我同意这应该从大的尺度上考虑,只是这么一个小园子能创造多少生态效益呢?ecological, sustainable design是不是只是一个噱头?为了在小尺度上试验生态设计而牺牲空间的诗意似乎成为现在的趋势,追求两者的完美结合是不是才是正确的方向呢?

这是在哪找的啊 好好哦

@iwtgta, 我晕。。这不是在哪找的,这是作者授权于我们发布在youthla上的。

@钟惠城, 哦 我又小白了 嘿嘿

YLA神通广大,不过我觉得能不能再神通一点,把这类授权文章加加密之类的,现在这样难保不会有人贴在别的论坛上之类的。

@vic, 不用加密,本来我们就不收费,是纯粹的学术净土。也希望大家能保持一颗纯真的心,不要乱用有知识产权的东西。:)

撇开整体规划不说,我对那里的植物喜欢得不得了。我就喜欢这种“野”的感觉,不像现在绝大多数公园里的植物那样被过度人工化了,变得很没生机。

@haliyingsuhua, 我们现在确实缺少真正能够让人有重新回到自然怀抱的有野味的公园。没有“野”味不仅是设计的问题,也有管理的问题。比如走在柏林的Tiegarten里面听到的是鸟声虫鸣,走在北京奥体森林公园里面听到的却总是喇叭里的音乐。可能更严重的问题不是现在公园里缺不缺少“野”味,而是再过二三十年或者三四十年,现在这些公园里能不能长出“野”味来。想桥园里的这种“野“味不知能否长久地持续下去。

-0- 求中文版

首先,我不是土人的设计师,对于具体的措施,很遗憾我也不了解。我只是补充了点我所知道而文章里没有表述的信息。

其次,对于空间的问题,想发表点看法。

1.空间的本质属性绝对是中性的,这是哲学基础,没有讨论的必要。对于空间的感知判断取决于观察者,“那么人在棺木之中和在广阔的原野之中的感觉都是一样的吗”,答案是否定的,但对于你我的审美偏好是一致的吗?答案也是否定的。

所以说,空间的本质是客观的,空间感知是主观的。虽然说,存在某种“大多数人的偏好”和“专家意见”,但对于一个环境的美学判断,视觉占有多重要的地位?

2.环境美学评价。

人的感知79%来自于视觉(如果这个数字没有记错的话)。所以设计,包括景观和建筑,向来聚焦在对虚体(空间)和实体的营造之上。空间感知是如何形成的?即人身处于实体围合的剩余部分之中(客观),通过视觉判断(客观),加上观察者的主观意识而产生(主观)。

而对于环境的审美判断是否仅依赖于视觉?答案越来越不言自明,说白一点,就是当一个地方更生态,更野的时候,即使视觉上不那么美,我也更倾向于偏爱它。当然除了生态,还有社会、经济等等其他的因素来左右这种选择。

3.信息的传达。

设计者试图表述的信息——媒介——观察者获取的意义(感知),这是通常的设计交流的流程,但这样的过程中不存在偏差吗?设计师你为什么确认公众能按你所设想的意向来感受环境。“作者开始写一本书,但是最后是由读者完成的。”这是歌德说的,读者有千千万,结局也有千千万。设计师费劲心机琢磨的那些东西,落到观察者那里可能完全不是那么回事。对于一个设计作品而言,你也不过是一个受众,你所感受到的,不过也是千万种可能性之一。

4.“园林本身就是空间的艺术。设计的过程就是推敲围合空间的过程,就是推敲植物、水、地形和其他构筑物如何围合空间的过程。”

这是视觉时代的价值观,新的价值观,建立在生态之上,这也是毋庸置疑的。

上纲上线上升了,说起话来真费劲。打这么多字,只是想说:设计师别总沉浸在自我臆想的那些东西中,还有很多其他的、更重要的,需要去关注,而且必须关注。

PS, 我不做设计。

@123, 受教了,我也不大懂,只是希望将这个讨论继续下去,引出更多如此精彩的评论。非常感谢!

@macross, 对空间的关注不是设计师的自我臆想,而是风景园林师区别于其他职业人员的职业特点。对于风景园林师来说空间是整合其他方面的起点,也是终点。不论对那些以视觉景观创造为本的设计师而言,还是对以生态、文化保育为本的规划师而言,都必须关注空间的营造和管理。如果撇开这个内容不谈,就不是风景园林师了。

但是园林设计的过程也不仅仅是推敲植物、水、地形和其他构筑物如何围合空间的过程。这个认识也很不全面。

@jacklion, 我以前也这么认为,不过来us看到许多这边的景观项目才发现,很多项目是生态主导的,实用的解决问题主导的。在某公园会发现一个很丑的水塘,周围都是野草野花。它很好的解决了排水和雨水管理问题,和工程结合的相当紧。而且维护也是低成本。这种设计看多了,就会很理解,很喜欢,比起一些过分考究空间,侧重点在美观的项目来说,关注生态,解决问题,低维护成本的项目感觉更高一层次。就好比曾经看的一个灯设计展,当许多设计者都关注风格,材质,造型的时候,有人侧重于节电,通过分析选择最省电而最大效用的设计;或者设计让人们开灯时做运动,宣传一种健康的生活理念,你会觉得这种设计更高一个层次。

当建筑开始走出现代主义,走向模糊与不确定时,景观开始走进一种新的唯“功能(生态)”思潮中,还真是滞后啊

看到思潮两个字俺笑了。。。

景观(应该是园林),过去关键是种树,现在一样关键是种树。土人所谓的“生态公园”其说白了就是忽悠市长,其实,每个公园只要多种点树,那不就是生态的么!(为城市提供氧气,改善小气候)。

看到目前大多数刚毕业的园林设计师,连树种都认不全,成天学搞建筑的谈什么思潮。。。只能说一个词——“附庸风雅”。

全是不透水的硬地,弄上树池种上树,那叫生态么?生态的本质在于循环,不透水的硬地,管道,就是在阻止雨水的循环。恐怕您就算参与到建筑界,也会说,建筑不就是盖房子嘛,成天学哲学搞什么思潮,附庸风雅而已。

“全是不透水的硬地,弄上树池种上树,那叫生态么。。”

答案是:可以叫生态。

生态与不生态没有明显的界限,只有相对而言,就算是不透水的硬地,种上树就比不种树生态。

再说了事实上,当前各设计院的园林设计师也并没有把‘生态’放在首位。

建筑,呵呵。。。俺不是那个专业的,不做评价。

你的逻辑似乎是这样的,事实上,当前闯红灯的人很多,所以宣传遵守规则只是一种嚼头?

“当建筑开始走出现代主义,走向模糊与不确定时,景观开始走进一种新的唯“功能(生态)”思潮中,还真是滞后啊”

呵呵,仔细看我说的,有没有说“不应该生态设计”呢,似乎没有吧?,我只是告诉你一个事实,园林没有走入你说的“唯生态思潮”。。。在中国园林界,也从来没有过什么明显的能上升到主义的思潮,园林也不太需要过多深奥的理论,这是个实操性很强的专业。

算了,谈这个其实也没啥意思,俺只是作为老鸟说一个客观的现实,作为新青年,有点学术梦想也还是好的。加油吧!

美国景观现在已经走到一个几乎唯生态论的境地了,中国景观现在是一片乱象,迟早也要走上那条路的。你看现在中国一样满地都是现代主义建筑。

美国司法界完全是三权分立,中国司法界现在是一片乱象,迟早也要走上那条路的。你看中国一样满地都是穿西式服装的。。。。。

呵呵,开个玩笑,美国的专业叫LA(土人译作景观),有很多生态环保规划的成分,而中国主流叫风景园林,职业是美化城市为主,看似是类似,其实有质的不同。不能同日而语。

桥*园……

瞧*圆……

成果的案例,施工完成后效果很好,很美

@sharmy, 功能太幼稚了,还是一个花园。

turenscape 的生态设计总是一团一团~~~“生态泡泡”—.—