Stoss Landscape Urbanism,一所由Chris Reed领衔的设计与规划工作室,赢得了2010年TOPOS景观奖。本文展示了Stoss在推动景观都市主义讨论方面的一些主要作品,以及该工作室的工作理念。

Stoss Landscape Urbanism, a critical design and planning studio headed by Chris Reed operates at the juncture of landscape architecture, urban design and planning, has won the Topos Landscape Award in 2010. Topos recognized Stoss for their theoretical and practical contributions to advancing the development of landscape architecture in dynamic systems, and to encourage discussion on landscape urbanism.

声明:此文为正式授权文章,已征得Stoss Landscape Urbanism同意在风景园林新青年(Youth Landscape Architecture)上发表,严禁转载。

Notice: This article is a reprinted version with the permission of Stoss Landscape Urbanism. Do not copy without permission.

2010 marks the fifth time the Tops Landscape Award has been granted. This time the distinction went to the landscape architecture firm Stoss Landscape Urbanism based in Boston, MA, USA. Topos recognized Stoss for their theoretical and practical contributions to advancing the development of landscape architecture in dynamic systems, and to encourage discussion on landscape urbanism. The critical design and planning studio headed by Chris Reed operates at the juncture of landscape architecture, urban design and planning. Stoss has won national and international recognition for landscape and urbanism projects rooted in infrastructure, functionality and ecology.

Landscape Urbanism In Practive

By Chris Reed

Stoss is at base a practice vehicle for research and experimentation, for testing broader ideas about landscape and the city within the context of the evolving theory on landscape urbanism. How do landscape urbanist ideas and agendas play out when you directly engage the systems, economies, constituencies, materials and media of the real world, the very stuff that forms the underpinnings of and context for the developing the? Or, more projectively, how might this direct engagement with critical design practices help to enrich and inform the theoretical discussions at hand?

Our landscape urbanist approach takes on three core issues of scale, time, and flexibility. We believe projects must be conceived and positioned relative to large-scale geographical, environmental and infrastructural systems, no matter if the site in question is small or large. Projects must tap into the evolving dynamics of ecological and civic or social systems in order to remain healthy and resilient. And projects must set up conditions for a wide range of uses and appropriations, for both those we can imagine now and those we cannot, in order to be viable immediately and for years to come. To achieve these ends, we favor a performance-based approach over one that is primarily physical, spatial, or visual. We are especially interested in how landscapes work: how they function urbanistically, socially, hydrologically, environmentally; how they reinforce existing city frameworks and how they invent new ones; and how they may support a range of complementary and sometimes contradictory civic programs across a multi-faceted, layered, and thickened urban field. Such an approach requires inventive analysis of the performance and programmatic requirements of social spaces and infrastructural or environmental systems: how big? How does it operate? In what configuration or orientation? And in what relation to its various parts? And it invokes wide-ranging, creative brainstorming and research-based methodologies that open up possibilities and potentials and allow for discoveries made along the way.

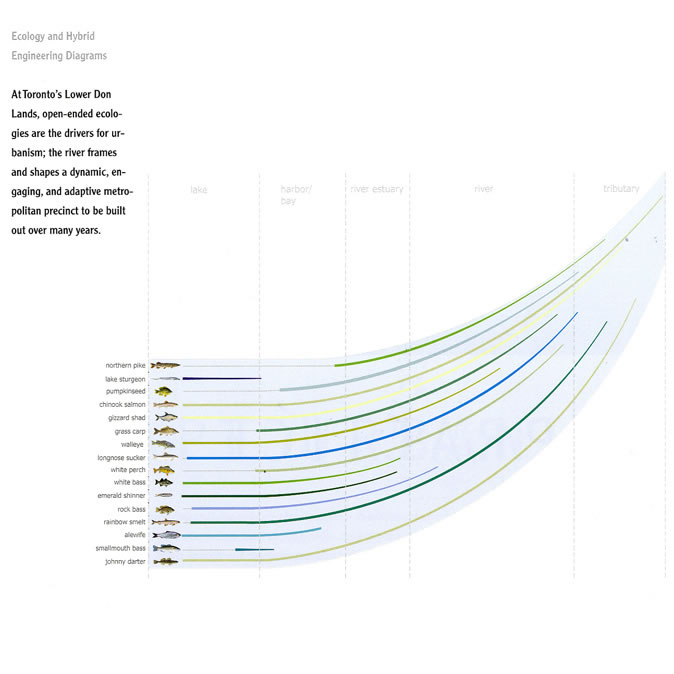

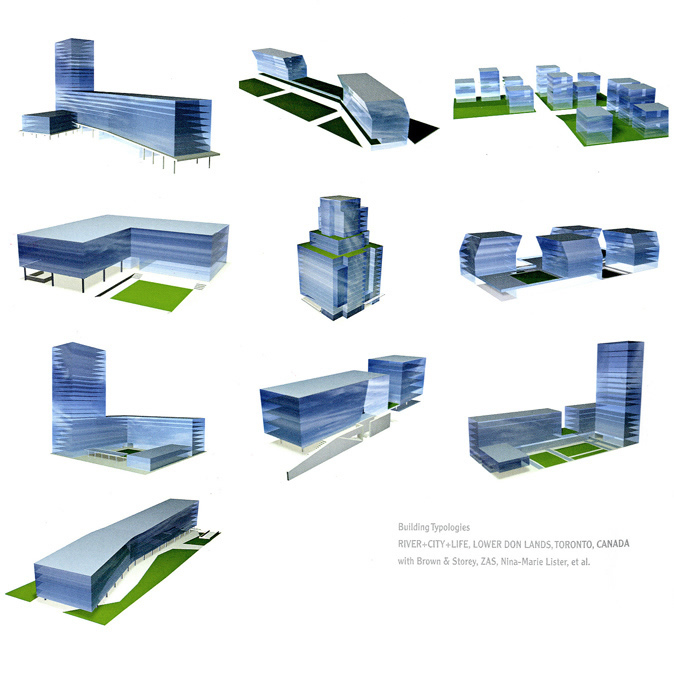

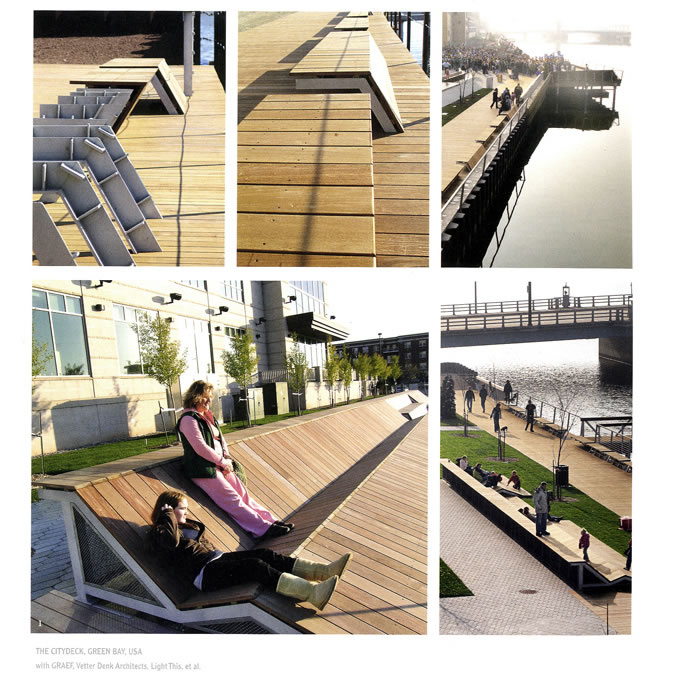

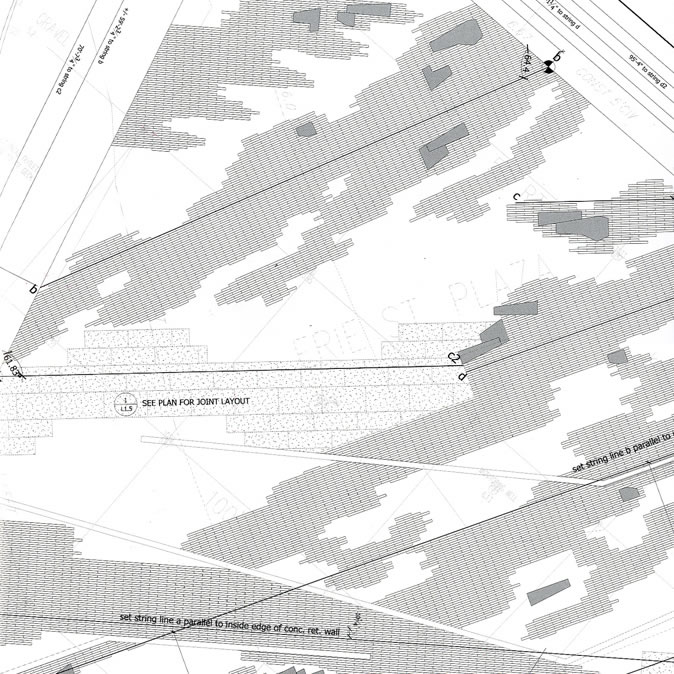

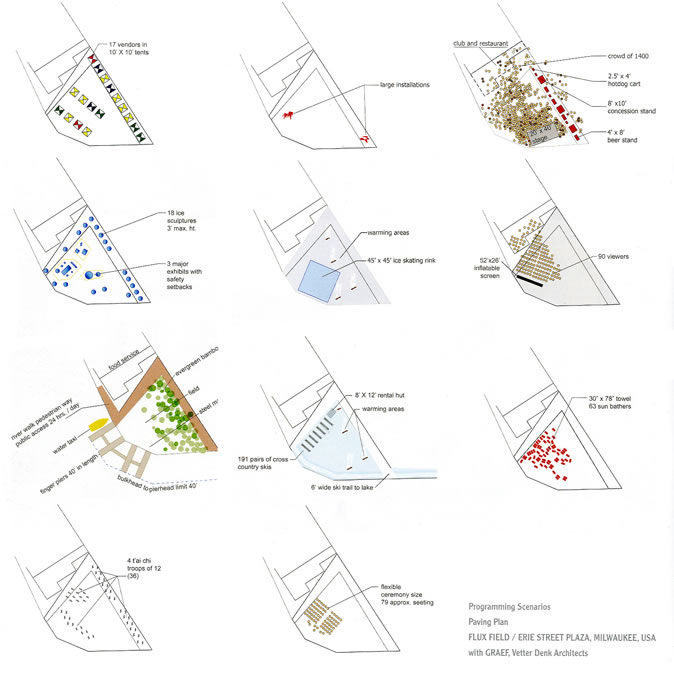

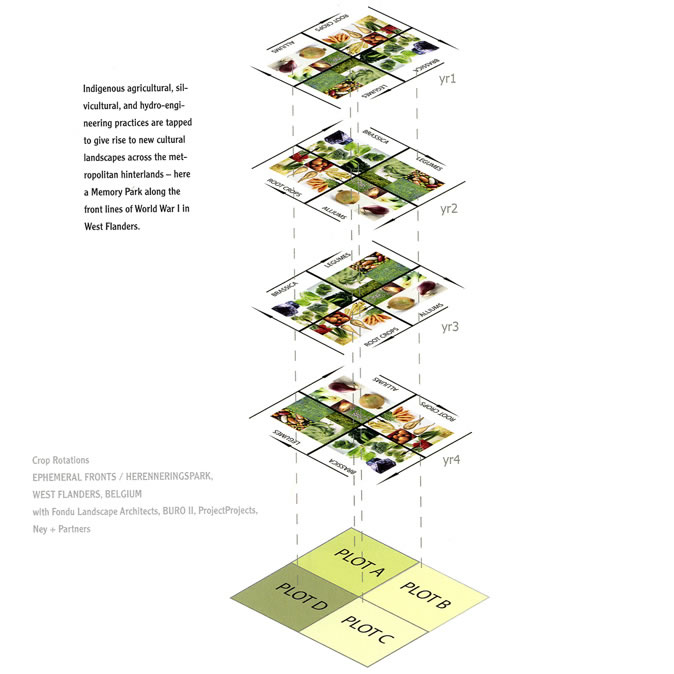

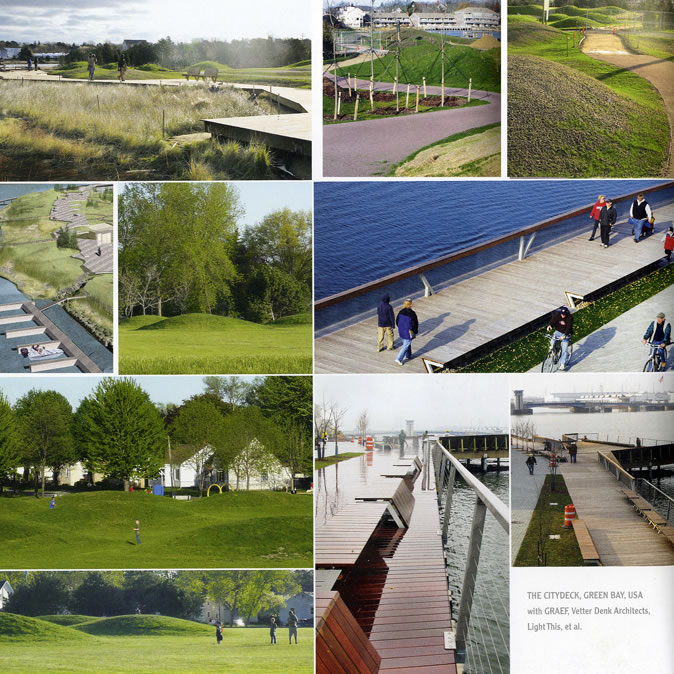

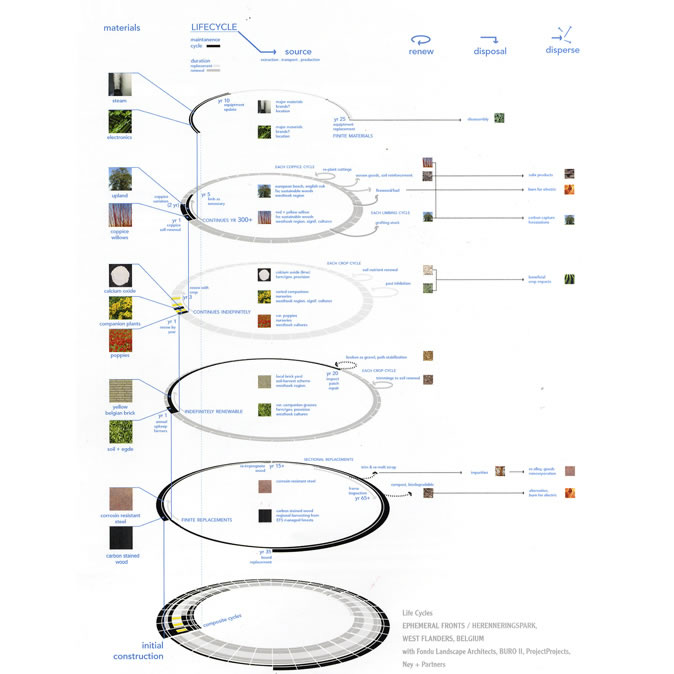

Such an approach yields new types of open space, landscape, infrastructure, and urbanistic strategies that address multiple functional, fiscal, and social/cultural goals simultaneously. These strategies are grounded in the particularities of local conditions, yet they are inventive and thickly layered in order to tap into broader trends and larger systems. And they privilege a regenerative approach to civic space and urban landscapes as complex, living, and evolving entities that are socially, ecologically, and fiscally sustainable through time. At larger scales, on complex sites, projects engage systems and networks that extend locally, regionally, and globally, and explore new techniques in drawing and representation. Proposals for time-based brownfield recovery strategies, like that at the Silresim Superfund Site in Lowell, Massachusetts, directly engage the technologies and timelines of environmental remediation, suppressed ecologies and diminished hydrologies still at work, and newly activated, dynamic stakeholder networks that can propel the work forward. Invited completion proposals for an ecology-driven urban framework and fabric (River+City+Life/ Lower Don Lands, Toronto, Canada) and for the social, ecological, and cultural re-calibration of 19th century drinking water infrastructures (Staging Mt. Tabor/ Mt. Tabor Reservoirs, Portland, USA) expand these ideas and allow us to test, concepturally, our own formulations of landcape urbanist ideas in large and complex public realms- at least as speculative proposals. At smaller scales, or with limited programs and budgets, projects become opportunities to focus laser-sharp on isolated issues that can collectively inform the broader investigations at hand. Many take the form of simple experiments with the materials and media of landscape. They include vegetal investigations into landscape and ecological succession (Eco-Lab and Bass River Park, both in Massachusetts, USA); mineral displays that measure the effects of wather and time on a field of colorful, textured aggregate piles (Stock-Pile at Radcliffe Yard, Cambridge, USA); synthetic installations that push the physical limits of recycled rubber surfaces (Safe Zone at the International Garden Festival in Quebec, Canada); and hydrologic cycles that integrate stormwater capture, cleansing and irrigation strategies, groundwater re-charge, and steam generation (Erie Street Plaza, Milwaukee, USA). Still others are studies in the ways people interact with open-ended designs, whether with earthen form (Farlin Park, Green Bay, USA and Safe Zone) or with material pattern and texture (Perkins Park, Massachusetts, USA and Erie Plaza). In all of these, extended monitoring and documentation of ecological, social, and/or hydrologic behaviors and effects inform ongoing research and project-making at multiple scales and on complex sites the world over.

Collectively, these inquiries and experiments are in their infancy- it’s not yet been 15 years since Charles Waldheim’s seminal 1997 conference in Chicago on landscape urbanism (to name but one touchstone), and we at Stoss have barely been at work a full decade. Many questions remain, for us and for others, relative to how landscape urbanism as a set of ideas and practices is played out- and refined, or even reformulated. After all, landscape urbanist thinking- flexible, responsive, adaptable, open-ended- has yet to be fully realized or tested at the scale of the city, in all its complexity. This will come. Just give it, and us, time.

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Photo Credit: Stoss Landscape Urbanism

什么时候有翻译啊

@*ff*, 为什么就不能读读英文的文章?

嘿嘿嘿嘿

很喜欢stoss的设计

最近不是刚拿下了minneapolis的水岸设计嘛!

在考虑要不要去那里实习

Minneapolis 水岸设计是 TLS/KVA 拿下的。据我所知,Stoss是难进的…

啊 记错了 谢谢提醒

stoss确实是进了final的 就是那个做了一溜激光束的