编者按:乌尔里克·波约姆(Ulrike Böhm)女士,赛如丝·扎黑立(Cyrus Zahiri)先生以及卡迪亚·班佛(Katja Benfer)女士是德国BBZL风景园林和城市设计事务所的三位创始人。与一般执业设计师不同的是,BBZL事物所的三位创始人都同时身兼教职,具有丰富的设计教学经验。结合自身的实践经验和教学经验,他们提出不仅应该教授学生设计的技巧,还应该向他们介绍设计的行为和思维特点,帮助学生了解设计的本质并在此基础上发展独立的个性化的设计策略。本文总结了他们在设计教学方面所依据的理论以及在教学实践中所采取的参与性更强的具体课程组织形式。希望它也能给我们的设计教学带来一些启发。

此文章为正式授权文章,已征得原文作者同意在风景园林新青年(Youth Landscape Architecture) 上翻译发表。文中图片除注明引用的之外,版权为原文作者所有。未经允许,严禁转载。

Notice: This article is translated and published with the official permission of the authors. The copyrights of the images within the article belong to the authors, except for those that marked as citations. Do not copy without permission.

作者:

乌尔里克·波约姆

赛如丝·扎黑立

卡迪亚·班佛

翻译:

吴祥艳,博士,中央美术学院建筑学院景观学系教师

刘静,北京清华城市规划设计研究院

党海霞,北京北京清华城市规划设计研究院

郭湧,清华大学建筑学院景观学系博士研究生

关键词:教学元素,技术,评价,反思,非言述性和默会性知识(2008年阿姆斯特丹designtrain 2008会议 2008.6.5-6.7)

(一)概述

设计可以被理解为不同物质性技巧与思维性技巧的集合和结合体。在物质性方面,存在着对各种多样人工制品进行形式化、转译与表达的可能方法,比如绘图和制作模型。在思维性方面,存在着对这些人工制品的比较、解释、定义以及评价。

在教育体系中物质无理性和思维精神性操作之间暗含的联系往往在教育体系中受到忽视。这种缺陷可以通过典型学术环境中的两种范例表现出来:

- 头脑风暴:学生们坐在一张白纸面前围坐在一张白纸面前,学生们被信心满满地认为保证道:“我只需要一个想法。然后我就会实现会实施它。”

- 集体评图:学生们的作业被排起来挂在墙上。一帮老师和教员坐在第一排批评这些作业。没有一个学生说一句话。

在第一种情景下,学生们会认为头脑风暴主要是思维性的。这种思维性的头脑任务必须先于在情况可以从在现实世界中将解决方案物质化之前之前首先完成。学生们相信“没有人工制品不是在有了想法之后才诞生的没有想法在前是不会形成人工制品的。”

第二种情景下,老师们认为他们的知识与经验可以简单地通过语言化的批评得以加以交流。他们相信:“没有什么专长,不是在专业技能的积累后才达到优异的标准的就没有出色的标准。”

上述的情况显示老师们和学生们都显而易见地在物质性操作和思维性操作之间进行了区分。这就直接导致了过于倚重语言化了的概念和和评价,也导致了学生和老师之间价值判断能力的不平等。

素材

上述主题在本文中会通过对设计课中运用的一些基本教学元素的介绍从更为具体的方面加以阐述。这些基本教学元素包括典型任务、成系列的作业流程以及不同的交流情景。所有这些元素都已经在柏林工业大学和卡塞尔大学的多个风景园林设计和城市设计studio中被常年运用。他们一直是频繁反思和不断调整的主题。

结果

- 如果设计既包含思维操作也包含物质操作将思维操作和物质操作相配合,那么在设计过程中就不能将的想法想法和它们的实现实施相就不会被分离。因而因此设计教育应该鼓励学生们对尽量多的不同观点和工作方法进行试验。这与探索不同的表现技巧相关联。从更广泛的意义上说,其他相关学科的观点可能也应该被涵盖进来。这样,一个需要动手的,以探索发现为导向的工作方法就可以建立起来。在这种工作方法下,解决方案的可能性可以通过不同参考框架见间的互相“转译”而出现。

- 学生们无庸置疑最应该占据坐在对站在评价他们自己的作品进行评价的位置上立场。他们会发展并维护自己的立场,与此同时,他们也要面对多种不同的质疑意见。如果鼓励他们强调自己的意见,他们的评价通常会比老师们的评价更为尖锐也更为深入。通过他们自身的内容评价,理论性的和实践性的主题(非言述性的和默会性的知识)就可以很容易地联系在一起。

结论

任务、作业流程成系列的作业以及交流的预设情景会影响学生和老师的角色扮演行为。它们会形成职业自我意识的产生的起点。为了发展和进一步完善设计教育中的学习过程,对我们而言就典型的教育元素以及内在的教育目标进行讨论是非常重要的。

(二)设计的方法

根据克洛斯(Cross,1984)的观点,设计的过程用语言是无法充分阐述的。“构成设计过程的认知和感知系统中只有相当小的范围的区域可以通过文字性的叙述加以修订。……设计师工作的方法可能是无法解释的,……原因很简单,因为这些过程处于语言描述能力的范围之外:用语言词汇,它们的确是无法描述的。”尽管有这些本质上的限制,通过下面的两个观点可以管窥“设计”的概念。

多样性与评价之间的设计

里特尔(Rittel,1992)将设计任务定义为“顽劣的问题”,以此和“温驯”的问题加以区别。“温驯”指可以对问题进行清晰的描述,并且具有可供检验的答案。与此相反,顽劣的问题无法被精确地或者令人信服地加以定义,因为他们的定义和可能的解决方案紧密关联在一起。

根据里特尔的观点,有两个方面可以被明显地看作是设计实践的组成部分:设计师创造多种不同选择性然后从不同选择中挑选特别适宜的应用方式适合的应用。这两个步骤间持续不断的转换贯穿了设计的全过程。

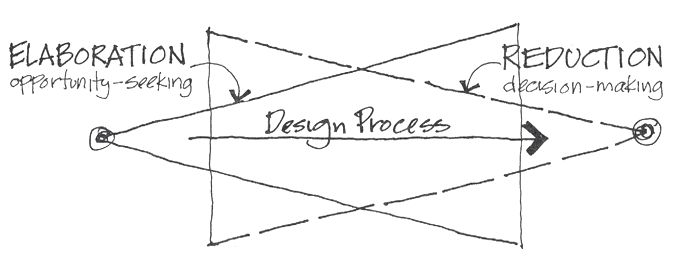

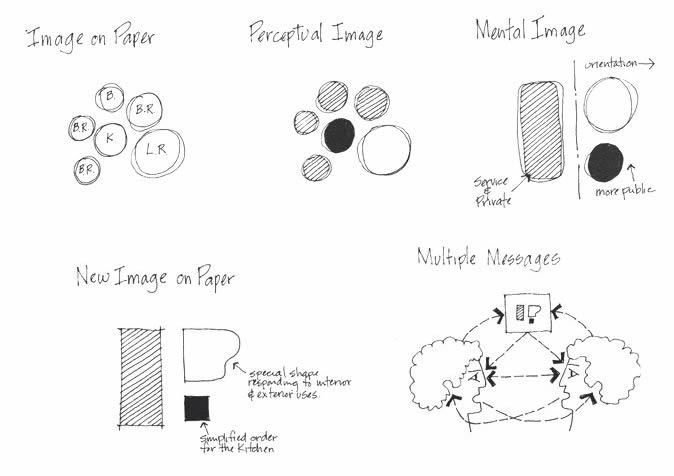

图1 设计的过程可以理解为创造多样性并从中进行选择的过程。图片引自Laseau, P. (1980): Graphic Thinking for Architects and Designers

作为多种技巧之合集的设计过程

根据语言学的框架,各种行为,诸如总结,组织,定位,整合,排序,构成,置入或者形成层级等动作的作用根据语言学的框架生发了产生了物质性身体和思维性的行动。如果设计的概念用以被用来与思维中的意向结合图像形成组合,它们就可以通过运用一种自身所熟悉的物质性身体动作行为来展现出所要欲传达传播的思想。如果没有对词语的这种比喻性的运用,思维意向图像的媒介几乎是不可能存在的。

显然,不同的语言和它们各自的运用无法在行为在动作与概念之间并没有形成清晰明显的区分分别。 甘舍特(Gänshirt,2007)引用凯穆普(Kemp,1974)的资料通过一个组合而成的生造合成词“Disegno”来描述这种二为一体的意义是如何发展的。“Disegno”一方面描述的是绘图的实际性的辅助能力,另一方面是指想象想象“它们所蕴含或创造的新世界”“内在于或有关于它们自身的新世界”的强大思维能力智力所具有的强大能力。

艾尔里奇(Ehrlich,1999)提出物质性身体行动和思维性行动之间在设计过程中不存在区别,而且这两种行动是等同的:“设计只用有通过身体活动身体和运用感觉感觉的运用时才可能发生。”

通过调查发展出来的设计方案通过探索发展出来的设计方案,始终处于表现、评价和使之多样化的变化转换中。对雷恩博和寇奇(Reinborn and Koch,1992)来说这就是说“当想法被以图示的方式固化,解决问题的新颖创造性条件随之呈现时,设计概念图示化的迷恋为解决问题创造了新的创造性的条件时,思考和绘图之间就发生了劳动的分化。”

二者无法在对此分化的感知和表现中被截然分开无法将二者截然分开。艾尔里奇(1999)强调说“一个设计成果的概念和紧随其后的它的物质化……,不能被看作独立的个体……”概念和它的物质化并不存在 “两者之间的前后时序和上下层级的关系。”

小结

对于里特尔来说,设计的焦点在于评价和决策的过程:“设计师或规划师的推理看上去像一个争论的过程设计师或规划师的推理看上去像一个推理的过程。”进一步而言,不同结果多样性的产生也取决于与对判断进行评价价值判断相关联。这种观点没有顾及到设计过程中设计发展和探索调查的阶段。

与此不同的是,艾尔里奇聚焦在作为设计方案发展过程的感知和表现方面。他对于物质性身体和思维性精神行为如何构成以及对于设计结果的基础是什么如何评价保留了弹性的余地。

对两种方法进行小结,我们可以大略总结出设计过程的两个组成部分。它们包括:

- 首先是产生想法概念的技术和技巧

- 其次是设计评价的标准

作为起点的学校学习经验

根据雷恩博和寇奇(1992)设计的发展“伴随着一个困难,并且总是漫长的在灵感和失败间转换的过程,在这个过程中从思维和概念上的混乱中生发。……这种直觉、概念和即时反思之间的波动虽然可能会导致概念的失败和受阻但是不应该受到排斥……”

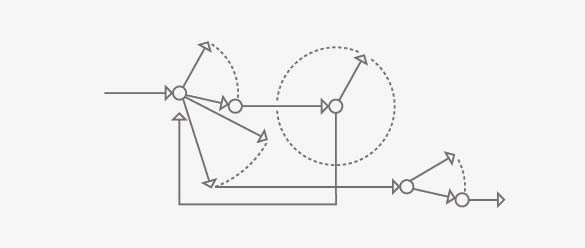

这里所提出的功能原则和感知设计的策略要求学生们具有一种意愿,可以接受心中事先没有清晰目标的解决方案。然而毕竟,理一个分析性的设计学习几乎不可能以直线性的和目标导向的方式展开。错误、错觉和挫折是设计过程不可避免的组成部分。例如,帕尔姆布姆(Palmboom,2004)指出“某种意义上,设计意味着发现创造性的错误以及在正确的时刻从直接性和狭隘性中脱轨。从来没有固定的拟补缺陷的形态,只有数不清的可能性。只用通过发现,选择,应用并弥合这种广泛的可能性,一个人才能找到一些自我证明的结果,这些结果让设计在外部世界中具有了合理性。这种让人着迷的游戏要求特别的胆量也要求耐性。”

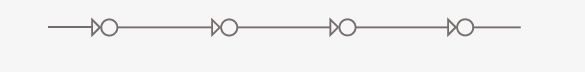

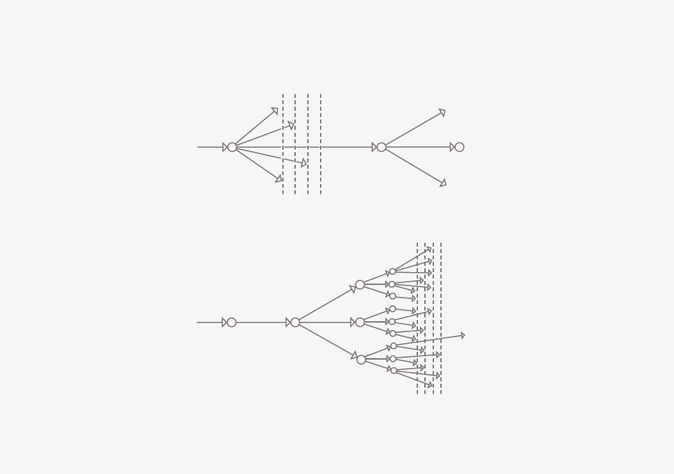

图2 直线的、以目标为导向的设计过程

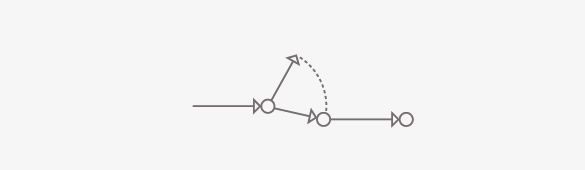

图3 包涵不确定性的探索过程的设计过程

图4 错误、错觉和挫折是设计过程不可避免的组成部分

然而,学校中学到的功能原则和感知设计的策略本身就被预设为目标导向的。它们是被清晰定义了的,而且往往具有清楚的评价标准。这种学习经验在开始就排斥“没有目标”的设计实践。持续地质疑和推翻个人设计策略的必要意愿可能会变得对大多数学生来说令人沮丧和生厌。只有少数学生可以独立地发展他们自己的设计策略。然而,我们应该通过逐渐介绍设计过程的办法来鼓励大多数的学生都做到如此。

在这篇论文中,我们会从上述的设计过程的两个方面进行更入微的观察,并把它们和教学元素相联系。第一部分阐述的是发现设计概念并开始实施的方法。第二部分阐述的是对设计方案进行管理和评价的预景。

(三)I.概念的产生与实现

理论起点

阿瑟(Archer,1984)将感知模型的能力和个人的表达形式相关联:“确实,和语言能力一样,我们相信人类具有感知模型的天生能力,以及通过草图,绘图,构成,表演等等进行表达的能力,这些是思想和推理的基础。”

如果人们接受阿瑟的关迪纳观点,那么用以解决空间问题的技巧组成了寻找设计方案的关键部分。如果没有这些技巧,就不可能展示、检验或者改善复杂的空间形式。雷恩博和寇奇将设计的过程描述为“手和脑的相互作用,是对可能方案的沉思和计划与形成概念的草图和图纸之间的相互作用。”在这种工作的方法下,“大量的的思维结果……必须不断地被以绘制在纸上的草图的形式存储下来,只有这样……头脑才能为新的想法和建议提供空间。”

为了就一个方案进行交流和改进,方案必须被可视化。通常,这一过程是通过草图、绘画、透视、模型以及解释性的文字来实现的。进行表现的具体技术和方法与每一种媒介紧密相关。这些包括诸如投影的方法,绘画和建模的技术或软件应用的工具等。它们决定了对一个特殊方案进行探索调查的可行性程度。

帕姆博姆认为绘图媒介转译和主导了设计的可能性。对他而言,“绘图不仅是想法和概念的展示。它们包含了一种可以对构成进行探索的意料之外的能力。”

图5 思维概念通过绘图成为可交流的设计内容。图片引用自:Laseau, P. (1980): Graphic Thinking for Architects and Designers

一个空间设计的表现几乎总是随着不同的媒介和表现方法而不同。事实可以证明,没有哪种媒介可以单独控制整个设计。为了检验额外的特点,一个设计必须首先被转译为另外一种表现语言。在每一次转译中,只有某些特定的方面会被保留;其他方面可能会被改变或者遗失。同时,其他的表达和改进便得变得可能。它们允许设计产生多样化并且在一种全新的视野下得以发展。

图6 不同的介质和表现方法为设计方案的发展带来更多可能性

帕姆博姆通过强调文字与绘图之间的关系指出了不同媒介之间的互动:“设计过程中存在文字与图像之间存在极端复杂的化学反应。这中种关系可不是精心规划的单行路,而是没有清晰对策可循的……文字和图像之间有一种空缺,其中必然预设了不确定性和歧义性──对应一个词语可以给出很多图像,而且一个图像可以被多种不同的词语所表述。”

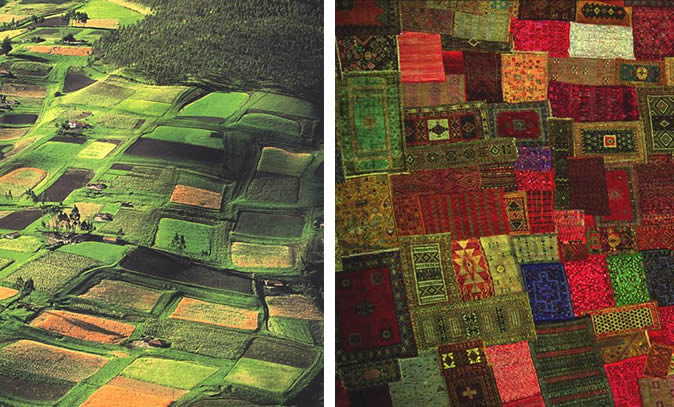

图7 文字与图像之间的空缺预设了不确定性和歧义性。图片引用自: Arthus Bertrand, Y. (2002), Earth from Above

任务流程

为了让上述理论具体化,我们提出如下的典型的设计任务流程系列,或称之为课堂作业。

实际上整个学期的课程被分解为可以便于管理的步骤。所有步骤都随着时间有序安排。它们进展规范,每周例行评图,开展讨论,要求完整。所有的作业都由学生个人或2至3人的小组来完成。

通常如果以一种简单的引介性的作业将给定的设计问题以一种简化的通常如果以一种简明的概述性的作业将给定的设计问题以一种简化的、轻松随意的形式加以阐述,这将非常有益。设计问题的相关组成需要有挑战性并能引发刺激。作业的时间是有限定的,这就强迫学生们必须快速反应并且形成自己的观点。作业的结果有助于形成和预设整个学期的目标,也会在学期课程结束后作为成绩的参考。

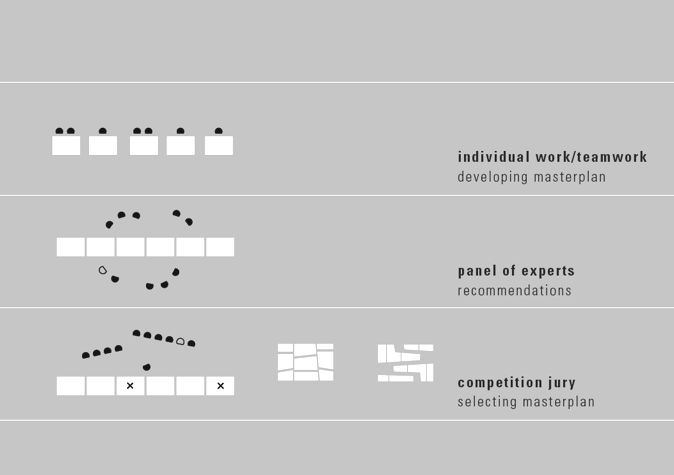

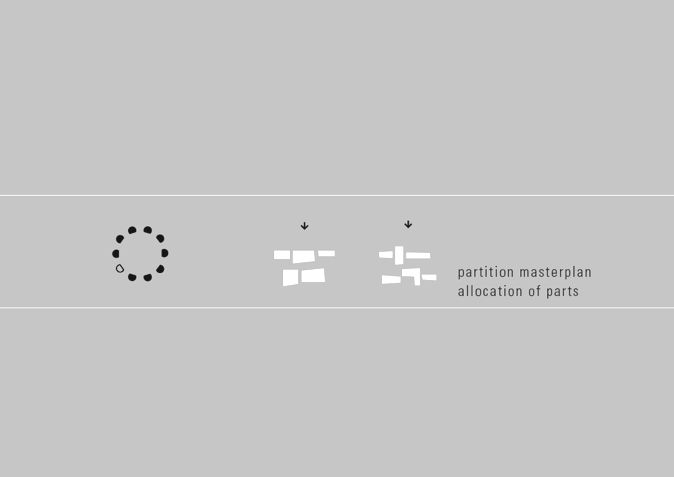

在学期的前三分之一时间内,学生们在一种竞赛的气氛下发展出不同的总体规划。为此设立了一种设计竞赛,竞赛评委会由学生和老师共同组成,通过竞赛挑选出最佳方案。这些随后被进一步划分为更小的区域以便发展更多的细节。通过这种方法,学生们的个人工作便可作为集合互相关联。通过这样的总体性途径,适应性的需要便应运而生。学生们可以学会调整他们自己的概念来适应更宏观的图景。

在整体过程中,相似过程的重复被有意避免。与此同时,会根据意料之外的干扰整合进一些不在事先计划之内的题外作业。这些题外作业可以很短,即兴练习。在德语中称为“Stegreife”(即兴表演),它可以帮助提高多样性,并且通过新鲜的想法丰富设计过程。这样的联系可以聚焦于更大的设计问题的某个具体方面这样的练习可以聚焦于更大的设计问题的某个具体方面,但是不一定非要与手上的主要任务相关联。相关的方面可以在与既存任务相独立的范围内加以调查。例如:

- 针对设计概念的练习(边界,拼贴,秩序,结构,材料……)

- 主题的汇集,场地印象,如光影,结构,场地利用,典型的场所和区域,边界……

- 结构的界定以及紧随其后的风景园林或城市设计相态的转译。

- 预测后续设计问题的练习(类型,入口和设施,平面组织……)

工作手段与主题的多样性

所有的设计作业都不可避免地与一定的媒介和表现手段相联系。在整个学期的课程中,会针对每个主题性的设计作业引进并试验多样化的手段。一些作业要求将快速转译为不同的媒介。纳入不同建模手段,数字和手工的可视化方法,或者图像化的抽象可以允许对设计问题进行更广泛的检验。同时,“意外之喜”和意义的转换也丰富了设计的发展。

最为核心的是,需要为所有的作业发展各方面的多样性。只有这样才能为评价和决策过程提供范围更广泛的备选可能性。多样性纪录了发展设计的过程所历经的一系列步骤。它们允许设计师在一条看上去没有希望的设计道路上前瞻后行并且重新发现或重新激活之前否定掉的方案。

图8 多样性纪录了发展设计的过程所历经的一系列过程

(四)II.评价

对实践的描述

根据Rittel(1992)的观点,评价是设计过程的关键部分。对大学水平的建筑师和规划师而言,现有的评价和选择的方法是通过“批评”的过程来演示的。学生们通过模型、草图和平面等形式汇报他们的设计构思。汇报过后,一群“批评家”根据作业的情况做出反应并且提出如何改进的建议和反馈。这群人通常由教授和受邀请的客人组成。

为了避免自己受到特别严厉的批评,哈佛大学GSD的学生们在网上用“河豚”为名公布了160条可供选择的应对方法。例如,第10号措施,标题是“模仿后现代”,它建议按照下面的台词回应:“把你的草图本翻个遍然后抬起头说:‘对不起,那些东西脚本里没有,你在看哪一页?’”

显然,学生们和教授们在评图时的冲突被看作是一种角色扮演。所有的网上建议都是连珠妙语,质疑了师生角色之间典型的对立与割裂。

这里所描述的这种交流情景具有明显的角色分配间的高度不对称性。只有汇报方案的学生参与到了与评委之间的讨论。其他的学生都保留了自己的评价。一方面,他们不愿意“在台上”破坏自己与同学之间的关系;另一方面,他们也不愿意使这个过程没有必要地延长。如果这种角色扮演总是这样重复下去,学生们就变成了过客,来宾或者消费者。他们感兴趣的焦点就只会是他们自己的作业。

除此之外,批评者角色的特点是由于绝对的“话语权”和排他性的词汇,他们具有特权化了的解释判断权。经常地,那些被采用的技术性词语都是很个人化的生造词汇,或者没有任何理论背景地纠结于空泛的讨论。更为甚者,评价的标准经常是个人态度与批评意见的衍生。

因为项目品质的保证掌握在教授的手中,学生们的评价标准就无人谈及因此也无法产生思考。

角色的变换

在上述的交流情景中,教授承担了对适宜设计方法进行评价和选择的所有责任。然而,课程的目的却应该是支持学生们自己的设计和决策过程。一段时间之后,他们应该发展起他们自己的品质意识和评价标准。

如前所述,批评的过程完全取决于角色的分配。只要通过一个简单的角色分配上的调转和他们相互的交流方式的转换,学生们就可以直接参与到确保设计项目质量的过程中。

课题的过程

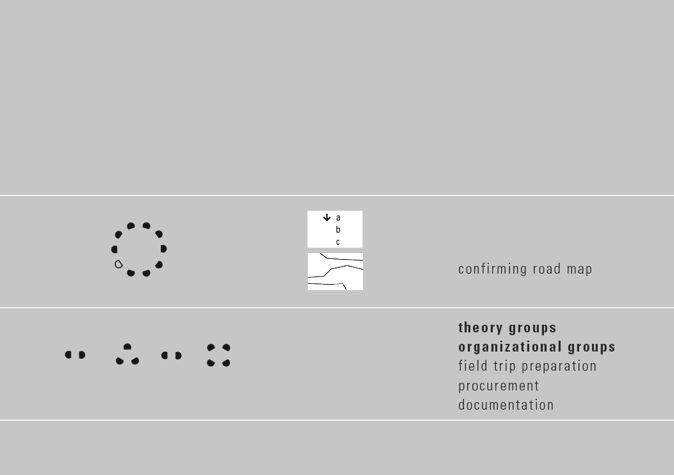

在第一次会面时,学生们和教授们会就课题的目标和相关的课程主题打达成协议。这些内容被所有参与者共同确认后,作为最高原则写在项目时间表或“路线图”上。

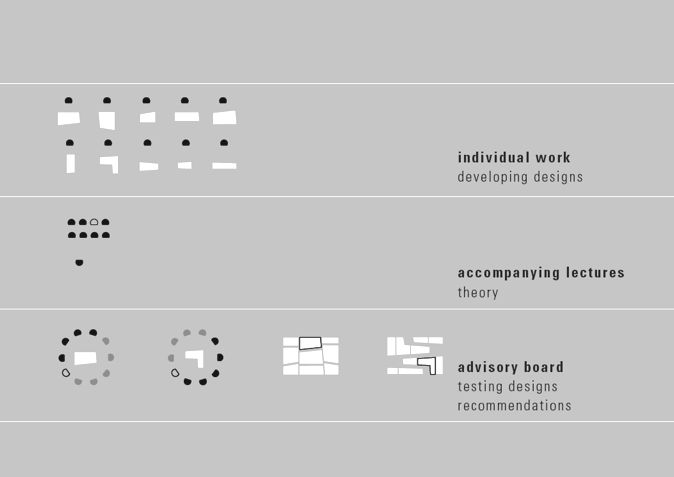

除处了设计小组之外,课程另外编制了组织团队和设计理论小组。组织团队负责诸如准备野外调查、采购材料,准备展览和归档作业等任务。设计理论小组准备简要的汇报,负责介绍与项目相关的各个方面的论点。在每周例行的讲座上,他们要向整个项目组介绍基本的概念和重要的设计理论。例如,以城市规划理论为例,他们需要查找并介绍 Sitte, Corbusier, Rossi, Lynch, Rowe, Humpert 和Sieverts等人的论著。为了促进对设计的工作过程和认知过程的反思,Arnheim, Rittel, Lawson或者Gänshirt的文章也被推荐作为阅读材料。

图9 设计路线图的确定与分组编制

作为设计过程的第一步,总平面图的设计和选择是在一个竞赛框架下完成的,学生们在中期汇报中扮演不同方面的各种专家角色。他们从多种不同的观点出发来检验设计的中期结果,比如决策者、投资人、市民或者规划师,接着他们会对每一个平面做出评价,给出评语。

竞赛的评委会是由学生们和教授们共同组成的。组委会的组成和他们投票的权重比例是由学生们在事前商定的。作为竞赛的结果,两个总平面图被评选出来,它们在学期的余下时间中会被进一步深化。这两个总平面都是由多个区域组成的,这些区域会由某个学生单独深化或者两人一组共同深化。为了保证总平面的贯彻,我们成立了两个咨询委员会。负责深化第一个总平面的学生们担任第二个组的咨询委员,反之亦然。在这种情况下,作为设计师的学生们就不会涉及评价自己的工作。教授们则担任两个组的咨询委员。

图10 独立工作、角色扮演与设计竞赛

竞赛的评委会是由学生们和教授们共同组成的。组委会的组成和他们投票的权重比例是由学生们在事前商定的。作为竞赛的结果,两个总平面图被评选出来,它们在学期的余下时间中会被进一步深化。这两个总平面都是由多个区域组成的,这些区域会由某个学生单独深化或者两人一组共同深化。为了保证总平面的贯彻,我们成立了两个咨询委员会。负责深化第一个总平面的学生们担任第二个组的咨询委员,反之亦然。在这种情况下,作为设计师的学生们就不会涉及评价自己的工作。教授们则担任两个组的咨询委员。

图11 选定总图与确定分工

设计概念需要每周一次通过草图、正图、图示和模型的形式向咨询委员会汇报。委员会需要对设计进行评议,必要时需要提出修改的建议。设计师是否能够接受委员会的建议则取决于其所采用的讨论技巧是否有足够的说服力。

图12 独立深化分区方案、集体理论学习、组成咨询委员会评议方案

委员会中的每位学生都要轮流做公开评议的主席。担任主席期间他需要对讨论的结果进行总结发言,还有作为主持人介绍发言人,并且控制发言时间。作为委员会的成员,教授们也要参与到上述的讨论形式中。为了防止对课堂讨论的过度影响,他们通常吧把自己的意见保留到最后。他们的任务就是在讨论中补充缺失的方面,澄清模棱两可的内容,平衡一边倒的指责,或者引入额外的不同的可能性。

图13 学生们既是设计师也是方案的评价者

图14 由学生组成的咨询委员会在评议方案

评价过程的效果

作为上述角色转换的结果,学生们已经出现了一系列明显的行为变化。下面我们就一一详细介绍。

设计的可交流性

专家或评论者的角色总是强调表达自身的观点。一直以来,学生在互相讨论作品时的压抑状况都被忽略了。 在评图过程中,整个团队都需要对设计作业有一定的认知和了解。这要求教授不再是一个人唱独角戏。仅仅依靠那些晦涩难懂的艺术家们的观点或者要求教师们更多的展现对设计的空间想象力,是不足以提升学生们的活力的。对大多数学生来说,他们更希望看到通过使用有效可行的方法,用细节来展现出自己的设计。

评价观点的多样性

学生们对同学的设计总是相对更苛刻。可同时,他们对同龄人的批评接受度也更高。讨论中某些观点一致的人会形成同盟。发表这些观点的学生会发现,可以通过对话找到更有说服力的平台。跳出学院式的条条框框,学生们将直面更广泛的评价。他们发现对一个设计的评定是可以通过众多不同的评价方式来进行的。如果设计确实较差,评判往往清晰且并无争议。相比教授们的评判,团队的意见不容易被过于随意主观的个体意见所支配。为了面对整个团队的审视,学生们必须扩展以及提升自己的设计。很明显,这个设计不仅仅只是完成了各项设计要求,同时必须使秉持不同态度的评判团队对它十分认可和满意。

反馈

所有的学生都发现自己不但是设计师,同时也是评价者。每一个人都在这两个角色中逐渐提升,因为他们必须在自己的同学团队面前为自己的设计做陈述或者答辩。在这两个角色的转换过程中,学生们对评论的敏感度也大有长进。很显然,每一个设计必须被一群决策者们了解并且接受。而对于设计者来说,领悟评论者们的观点和目的,以及考虑团队的多变性等,同样至关重要。

职责

设计主题、教学目标和课时表,这些都将参考学生们的意见。 如此一来,他们的参与意见将与所有决定直接关联,学生们将自己轮流承担这一公共职责。学生们可以构建自己想要的教育模式,走向自己树立的理想目标。这一计划最主要的成果就是,学生们由于自身对课程内容的制定有所承担,因此产生了很强的主观能动性。

强项与弱项

如上所述,学生们承担着多重角色:设计者、专家、演讲者、指导者、评论委员会中的委员、组织者、决策者、主持人等等。他们需要投入到这些不同的角色团队中,并且常常和不同的人进行辩论。每个人的特点和强项决定了她将会擅长于某一个角色。在其他角色里,她会有很多机会提升自己的弱项,并挖掘出新的潜力。

理论与实践的联系

通过评价自己的设计,学生们开始体会到树立评价标准的重要性。教科书成了团队用来引用专业术语、理论概念,甚至争论用词的重要道具。因此,学生们对目前课程的关注也大大提高了。在指导团队的讨论会上,个人的设计成果中应用的理论是否合理与切题,这一点需要慎重评价。现在,学生们积极扩展他们的专业词汇,并且能在相应的理论背景中应用这些词汇。同时,通过学习现有的理论,学生们可以将自己的设计理念变得更加的多样化,更加的丰富。

教授的角色

随着环境的改变,教授所扮演的角色也随之发生改变。教授应放弃固有的传统的领导者角色,承担建议者和指导者的角色。当教授不再是评图课的中心焦点时,她就会有机会静下来仔细审视讨论的过程。这样,她会尽早的发现问题,并且有充分的时间去找到解决的方法。由于评图过程中的很多方面已经由学生开始进行讨论,教授只需使之细化即可。她能指出疏漏的地方,使不清晰的观点更明确或提出可供参考的改进方法。学生已经经过讨论确认的观点,教授们可将其串联。通过建立一个共同的概念框架,教授放弃了她的话语权优势。大家都明白她的地位,这是不可否认的,她不必对此有所怀疑再来证明她的定位。如果她反对某个小组全体一致的想法,则会产生更多讨论的机会。当专业术语应用于理论环境中,已给定的概念之后的想法对于所有参与成员仍保留着清楚易懂性和可辩论性。

(五)总结

教学原理在这里展现的是应该如何使学生缓和的进入工作和设计的认知过程。原理的本质方面包括以下内容:

- 学期计划的结构和复杂设计的构想作为一系列的相关任务来分配。

- 在设计过程中对特殊的工作技巧所具有的潜力及局限进行敏感地感知。

- 理论概念和评价过程的连接。

- 以允许学生们思考他们的设计过程为目标建立各种交流的场景。

随着上述的角色分配转换,学生们经历了在能力和积极性上的有效的增强。这个也同样适用于在创造过程中缺乏经验和自信的学生。

对本文所述的教学情景受到多种理论的启发,也得益于在教学工作营和研讨会背景下的众多讨论。我们相信在这一领域的教学中仍有很大的探索空间。因此我们认为在一个更加广泛的背景下交换我们彼此的设计教学经验和知识具有重要意义。

THE DESIGN PROCESS – Between imagination, implementation and evaluation

Keywords: Didactical elements, techniques, evaluation, reflection, explicit and tacit knowledge

(Designtrain Congress 2008 Amsterdam 5.6-7.6.08)

INTRODUCTION

Design can be understood as a collection and combination of different physical and mental techniques. On the physical side, there is the formulation, translation, and presentation of possible approaches to various artefacts, such as drawings and models. On the mental side, there are comparisons, interpretations, definitions and evaluations of such artefacts.

The implied link between physical and mental operations is often neglected in educational settings. This deficit may be illustrated by two exemplary situations from the typical academic environment:

- Brainstorming: sitting before a blank page, the student is assured: “I just need an idea. Then I will implement it.”

- The group critique: The students’ works are lined up along a wall. Sitting in the front row, a panel of lecturers and faculty members critiques the works. Not one student says a word.

In the first scenario, the student assumes that brainstorming is mostly mental. This mental task must first be completed before the solution may be materialized in the physical world. The student believes: “No artefact without an idea first.”

In the second scenario, the teachers assume that their knowledge and experience may be simply communicated in the form of a verbalized critique. They believe: “Without expertise, there is no standard of excellence.”

These statements demonstrate that both teachers and students starkly differentiate between physical and mental operations. This is directly linked to the over-valuation of verbalized concepts and appraisals and an unequal allocation of value judgement skills between students and teachers.

Material

The thesis presented above shall be illustrated in detail by introducing some basic didactic elements used in design classes. Among those elements there are typical tasks, sequences of assignments and different communication-scenarios. All elements were used over years in several design-studios in landscape architecture and urban design at the Berlin Institute of Technology and at the University of Kassel. They were subject to an intensive reflection and adaptation.

Results

- If design incorporates both mental and physical operations, ideas and implementation cannot be separated within the design process. Design education should therefore encourage students to experiment with as many different viewpoints and working methods as possible. This is linked to exploring different presentation techniques. In a broader sense, perspectives of other related disciplines might also be included. A hands-on, discovery-oriented working method is to be established, in which potential solutions may arise in the ‘translation’ between different referential frameworks.

- Students are most definitely in a position to evaluate their own work. They develop and defend their own positions – at the same time, they are confronted with a variety of different opinions. Encouraged to articulate their opinion, their assessments are often sharper and more sophisticated than those of their teachers. Through their involvement in quality assessments, theoretical and practical topics (explicit and tacit knowledge) may easily be linked.

Conclusions

Tasks, assignment sequencing and communication scenarios influence the role-playing behaviour of students and teachers. They generate a starting point from which a professional self-image is to be established. To develop and refine the learning process in design education, it is important to us to discuss typical didactical elements and the underlying educational objectives.

APPROACHES TO DESIGN

According to Cross (1984), the design process may only be insufficiently captured with words. “Only a relatively small (and perhaps insignificant) area of that system of knowing and conceiving which makes designing possible may be amenable to verbal description. (…) The way designers work may be inexplicable, (…) simply because these processes lie outside the bounds of verbal discourse: they are literally indescribable in linguistic terms.” Despite these substantial limitations, the following two positions seek to approach the concept of ‘design.’

Designing between Variation and Evaluation

Rittel (1992) identifies planning assignments as ‘wicked problems,’ distinguished from ‘tame’ ones, which offer clear descriptions of the problem and checkable answers. By contrast, evil problems cannot be precisely or conclusively defined, because their definitions and possible solutions are closely linked together.

According to Rittel, two processes may be distinguished as part of the design practice: the designer generates alternatives and then selects especially suitable applications from a set of alternatives. Both steps continuously alternate during the design process.

The Design Process as a Collection of Techniques

Operations such as summarizing, arranging, positioning, composing, ordering, structuring, embedding or creating hierarchies, constitute physical or mental actions depending on the linguistic context. If design concepts are used in combination with a mental image, they illustrate thoughts to be transmitted by using a familiar physical operation. Without this metaphoric use of words, the mediation of mental images would barely be possible.

Obviously different languages and their respective usage do not make sharp distinctions between operations and concepts. Referring to Kemp (1974), Gänshirt (2007) describes the development of this twofold meaning by coining the term “Disegno.” “Disegno” describes on the one hand the practical facility of drawing, on the other hand, the power of the intellect to imagine “new worlds in and of themselves.”

Ehrlich (1999) implies that there is no differentiation between physical and mental operations during the design process, and that the two operations are equal: “Design is only possible through the activity of the body and the use of the senses.”

Design solutions developed during an investigation, are in constant interplay between representation, evaluation and variation. For Reinborn and Koch (1992) „a division of labor between thinking and drawing develops, as the graphic fixation of ideas creates new creative conditions for solving problems.”

To conceive and to represent thus cannot be distinguished sharply from one another. Ehrlich (1999) suggests that “the idea of a design achievement and its subsequent materialization (…), may not be seen as independent entities (…).” Idea and materialization do not exist in “chronological or hierarchical relationship to one another.”

Synopsis

For Rittel, the focus of design lies with the evaluation and decision- making process: “The reasoning of the designer or planner appears as a process of argumentation.” Furthermore, the production of alternatives is linked to value judgments. This point of view disregards the development and investigation phase in the design process.

Ehrlich, on the other hand focuses on conceiving and representation as a process in the development of design solutions. He remains flexible on how physical and mental operations may be combined, and on what basis a design solution may be evaluated.

In a synopsis of both approaches, two components of the design process may be specified. These include:

- on the one hand techniques and skills for the generation of ideas,

- and on the other hand criteria for design evaluation.

The learning experience in school as starting point

According to Reinborn and Koch (1992) designs are developed “in a difficult, indeed often tenacious process of alternating inspirations and failures, which arise from a mental and conceptual chaos. (…) This fluctuation between intuition, conceptual ideas and reflections thereon, which may lead to failure and the rejection of ideas (…) should not irritate (…).”

The functioning principle and cognitive design strategy outlined here require a willingness of the student to accept a solution without first having a clear objective in mind. However, an analytical design study rarely proceeds as linear and goal-oriented. Mistakes, misconceptions and setbacks are an inevitable part of the design process. Palmboom (2004), for example, notes that “in a sense, design means discovering the creative error and deviating from the straight and narrow at exactly the right moment. There are no fixed patterns down in the gap, just countless potentialities. Only by discovering, selecting, using and interweaving this vast range of possibilities does one – eventually – reach something self-evident which legitimises the design to the outside world. This fascinating game requires a high degree of boldness, as well as patience.”

However, the functioning principles and cognitive design strategies learned in school are predominantly goal-oriented. They are well defined and usually have clear evaluation criteria. This learning experience at first contradicts the idea of employing an ‘aimless’ design practice. The necessary willingness to constantly question and revise personal design strategies can become rather tiresome and discouraging for most students. Only a small number of students are able to independently develop their own design strategies. The majority of students should however be encouraged by means of a gradual introduction to the design process.

In this paper, we will take a closer look at both components of the design process described above, and link each with didactic elements. The first section presents approaches to finding ideas and initiating their outworking. The second section presents scenarios for the management and evaluation of design proposals.

I. IDEA GENERATION AND REALISATION

Theoretical point of departure

Archer (1984) couples the ability of cognitive modelling with individual forms of expression: “Indeed, we believe that human beings have an innate capacity for cognitive modelling, and its expression through sketching, drawing, construction, acting out, and so on, that is fundamental to thought and reasoning as is the human capacity for language.”

If one follows Archers view, the techniques used to solve a spatial problem constitute an essential part of finding a solution. Without these techniques, it is not possible to illustrate, examine or modify complex spatial situations. Reinborn and Koch (1992) describe the design process as “interplay between head and hand, between contemplation and cogitation of possible solutions, as well as sketching and drawing initial conceptions.” Within this approach to working, “the abundance of mental solutions (…) must continuously be “saved” in the form of a sketch on paper so that (…) the head has space for new ideas and suggestions.”

In order to communicate and verify a solution, it must be visualised. Frequently, this is done in the form of sketches, drawings, perspectives, models and explanatory texts. Specific techniques and methods of representation are associated with every medium. These include e.g. projection methods, drawing and modelling techniques or the tools of software applications. They determine the range of investigative possibilities for a particular solution.

Palmboom (2004) describes the interpretation and manipulation possibilities affiliated with the medium of drawing. For him, “(Drawings) are more than just illustrations of ideas or concepts. They contain a composition that can be searched for its unsuspected capabilities.”

Representations of a spatial design are almost always spread out over different media and representation methods. Evidently, no one medium alone can capture the entirety of a design. In order to examine additional features, a design must first be translated into another representational language. With each translation, only certain aspects will be preserved; others will be altered or even lost. At the same time, other possibilities for representation and adaptation become available. They allow the design to be varied and developed in an entirely new light.

Palmboom (2004) describes the interaction between different media by emphasizing the relationship between words and drawings: “During the design process there is an extremely complex chemistry between the words and the images. This is not a matter of carefully regulated one-way traffic – there is no clear recipe to be followed. (…) There is a gap between the words and the images, in which uncertainty and ambiguity must predominate – for one word can give rise to various images, and one image can be put into various different words.”

Task-Sequencing

To substantiate the premises described above, a typical series of design tasks, or classroom assignments, are outlined as follows.

The actual assignment is divided into manageable steps over the course of the semester. All steps are sequentially built up over time. They are regularly processed, reviewed weekly, discussed and completed. All assignments are handled individually or in groups of two or three students.

It is often helpful to begin with a brief introductory assignment that presents the given design problem in a simplified, playful and casual manner. The corresponding formulation of the design problem should be provocative and stimulating. The processing time is limited, thus forcing the students to react quickly and to form their own perspectives. The results of the assignment help formulate and anticipate the goals of the semester, and may always be referred to over the course of the semester.

In the first third of the semester, the students develop master plans for an area in a competitive working atmosphere. A design competition is established in which a jury of students and teachers select the best plans. These are then subdivided into smaller areas to be developed in more detail. In this way, the students’ individual work is collectively interrelated. Through this overall approach, the need for adaptation arises. Students learn to adjust their individual concepts to fit the bigger picture.

Within the overall process, the repetition of similar processes is averted. At the same time, excursive assignments are suited to unexpectedly interrupt the predetermined schedule. Such excursive assignments could be short, impromptu exercises, so-called „Stegreife,“ which help provide diversion and enrich the design process with fresh new ideas. Such exercises may focus on a specific aspect of the greater design problem, but are not necessarily linked to the main task at hand. Relevant aspects may be investigated in isolation from existing commitments. These include:

- Exercises dealing with design concepts (borders, collage, order, structure, material,…)

- The collection of thematic, on-site impressions, such as light and shadow, structures, site use, typical places for the area, borders…

- The identification of structures and their subsequent translation into landscape architectural or urban design patterns.

- Exercises that anticipate pending design questions (typology, access and infrastructure, ground plan organization, …)

Working techniques and variations on the theme

All design assignments are inevitably linked with certain media and presentational techniques. Over the course of the semester, various techniques will be introduced and tested out for each thematic design assignment. Some assignments call for the rapid translation of the design concept into different media. The inclusion of different model building techniques, digital and manual visualization methods, or photographic abstraction allows for a broader examination of the design problem. At the same time, “happy accidents” and shifts in meaning enrich the development of the design.

In essence, multiple variations need to be developed for all assignments. In this sense, selections can be made from a larger pool of possibilities during the evaluation and decision-making process. The variations document the development of the design process over a series of steps. They allow the designer to move back and forth within a seemingly hopeless design path and to rediscover or reanimate previously neglected solutions.

II. EVALUATION

Description of the practice

According to Rittel (1992), evaluation is an essential part of the design process. The established method of evaluation and selection for architects and planners at the college level is demonstrated by the ‘critique.’ Students present their design ideas in the form of models, sketches and plans. Following the presentation, a panel of ‘critics’ reflect on the state of work and give advice and feedback on how to proceed. The panel usually consists of professors and invited guests.

In order to protect themselves from particularly harsh critiques, Harvard Graduate School of Design students compiled a list of 160 possible responses, which they published on-line under the name „Blowfish.“ For example, proposal No. 10, boasting the caption “Postmodern simulation,” suggests reacting with the following line: “Leaf through your sketchbook and then look up and say, “I’m sorry, that’s not in the script. What page are you on?”

Obviously, the confrontation that arises between students and professors during a critique is perceived as role-playing. All suggested reactions deliver their punch lines by questioning the typical division of roles between teachers and students.

This described communication setting is characterized by a highly asymmetrical distribution of roles. Only the students who are presenting work engage in discussion with the panel. The other students withhold their comments. On the one hand, they wouldn’t want to strain the relationship with their fellow classmates „on stage“ – on the other hand, they wouldn’t want to prolong the process any longer than is necessary. If this role-playing is constantly repeated, the students turn into passengers, guests or consumers. The focus of their interest is mainly on their own work.

The role of the critic, on the other hand, is characterized by her privileged interpretive jurisdiction, by an unlimited „right to speak“ and an exclusive vocabulary. Frequently, the technical terms that are used are private neologisms or hover over the discussion without any theoretical context.17 Moreover, the qualifying criteria are always derivative of the personal attitude of the critic.

Because the quality assurance of the project lies in the hands of the professor, the evaluation criteria of the students remains unspoken and thus uncontemplated.

Shifting the roles

In the communication setting described above, the professor assumes all responsibility for the evaluation and selection of appropriate design approaches. The goal of the course however, should be to support the students in their own design and decision- making process. Over a period of time, they should develop their own sense of quality and set of evaluation criteria.

As described, the process of the critique depends entirely on the distribution of roles. Through a simple shift in role assignments and their related forms of communication, the students can directly participate in the quality assurance of design projects.

The following example illustrates this procedural change.

Project proceedings

At the first meeting, students and professors formulate the project goals and relevant course topics together. This culminates in a project timetable, or „road-map,“ confirmed by all participants.

In addition to the design groups, alternating organizational and design-theory groups are formed. The organizational groups take on tasks such as field trip preparation, materials procurement, exhibition preparation and documentation of the work. The design- theory groups prepare brief presentations on various aspects of the project theme. In accompanying weekly lectures, they introduce the whole group to basic concepts and important design theories. In the context of urban planning theory, for example, appropriate articles are found in the writings of Sitte, Corbusier, Rossi, Lynch, Rowe, Humpert and Sieverts. To stimulate reflection on the working and cognitive processes of design, articles by Arnheim, Rittel, Lawson or Gänshirt are suggested as appropriate reading material.

As the first step in the design process, master plans are created and selected within a competitive framework. Students assume the roles of various experts during an intermediary colloquium. They examine the interim results from the point of view of municipal authority, investor, citizen, or planner, and come up with estimations and recommendations for each plan.

A jury is made up of students and professors. The composition of the jury and the proportional weight of their votes are determined beforehand by the students. As a result of the design competition, two master plans are selected, which will be handled in detail throughout the remainder of the semester.

Both master plans consist of areas, which are to be worked on individually or in pairs. To ensure compliance with the prerequisites of the master plans, two advisory boards are established. Students involved in the detail planning of the first master plan are members of the advisory board for the second master plan and vice versa. In this way there are no contradictions between the interests of the students as designers and their work as members of the advisory board. The professors are members of both boards.

Design ideas are to be presented weekly to the advisory board in the form of sketches, drawings, diagrams and models. The board is to evaluate the designs and where necessary suggest adjustments or changes. Whether the designer follows up on the board’s suggestions depends on the persuasive power of the ensuing arguments.

All referenda are chaired in turn by each student on the advisory board. Among the chair’s tasks are the concluding summarization of discussion results, the moderation of speakers and the monitoring of speaking-time limits.

As members of the advisory board, the professors are also integrated into the described discussion format. In order to not overly influence the course of the discussion, they often save their input until the end. Their task is to supplement the discussion with missing aspects, to clarify obscurities, to contradict one-sided judgements, or to introduce additional alternatives.

Consequences for the evaluation process

Several changes in the behaviour of the students have been observed as a result of the described shift in roles. These are described as follows.

Communicability of Design

The role of an expert or critic involves the ability to express her opinion. This eliminates the typical inhibition of students to discuss each other’s work.

For the evaluation process, the entire group must be able to recognize and understand a given design. This requirement is no longer that of the professor’s alone, as she is no longer the sole addressee of the presentation. The attitude of the ‘misunderstood artist’ or the appeal to the ‘imaginative powers of the teacher’ can simply not hold up to the group dynamic of fellow students.

For the students it goes without saying that their designs are to be presented in detail, using all available techniques.

Variety of Opinions

The students’ criticism of their classmates’ designs are comparatively tough. At the same time, they are more receptive to the criticisms of their peers.

Alliances of opinions arise during the discussions. Fractions of students who share similar positions find common ground in the dialogue. Instead of one school of thought, students are confronted with a wide range of opinions. The student recognizes that a design solution can be assessed in a variety of different ways.

In the case of weak designs, critique usually tends to be clear and unanimous. In contrast to the judgement of a professor, the critique of the entire group is not subject to individual capriciousness or subjectivity. Confronted by the judgement of the entire group, the student is thus forced to develop and improve her design choices.

For the overwhelming approval of a design, it is clear that the quality of the solutions must not only fulfil different prerequisites, but must also equally satisfy and convince a group of critics with widely diverging attitudes.

Reflection

All students find themselves in the role of the designer, but also in the role of critic. They each develop individual positions, which they must introduce and defend before a panel of their peers.

The change in roles also heightens their sensitivity to criticism. It becomes clear that any proposed design must be understood and endorsed by a group of decision-makers. It is also critical for the designer to understand the criteria and motives of her peers and to take the dynamics of the group into account.

Responsibility

The project topics, educational goals and semester timetable are all developed with the students. In this way, all decisions directly involve the students and they in turn assume a shared responsibility for the project results. The students thus shape their own education and thereby develop their own objectives. From the newly acquired responsibility for the course content, a strong sense of motivation emerges as the main effect of the process.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Within the described settings, the student takes on different roles: as producer, as expert, as speaker, as advisor, as jury member, as organizer, as decision-maker, as moderator… The student must orient herself within different group settings and thus be able to constantly renegotiate with new people. According to her strengths, she will successfully fulfil certain roles. In other roles she will have the opportunity to improve weaknesses and discover new potentials.

Relationship between theory und practice

Through the act of evaluating their own designs, the students begin to appreciate the value of evaluation criteria. The accompanying presentations of theoretical texts provide the group with specialized terms, concepts and possible lines of argumentation. Accordingly, the students are highly concentrated on the content presented.

The suitability and relevance of the offered theories are scrutinized on the basis of individual design solutions during the meetings of the advisory board. Here, the students develop their own vocabulary and are able to apply it within a corresponding theoretical context. At the same time, the presented theories allow the students to diversify and supplement their own design ideas.

Role of the professor

With the change in setting, the role of the professor is also changed. The professor gives up certain characteristics of traditional leadership roles and takes on the attributes of advisor or coach.

As the professor is no longer the central focus of the event, she has the opportunity to sit back and scrutinize the discussion process. She detects problems early on and gains enough time to develop alternative perspectives. Since many aspects of the process have already been brought into the discussion by the students, the professor’s input may be much more precise. She can introduce missing points, clarify grey areas or offer alternatives. The positions already broached by the students offer the professor possibilities for connecting ideas.

By establishing a common conceptual framework, the professor forfeits part of her linguistic advantage. Her role is understood by all, undeniably, and in case of doubt she must even justify her position. If she contradicts the unanimous opinion of the group, the opportunity for intensive discussion arises. As the use of technical terminology is always embedded within a theoretical context, the ideas behind any given concept remain transparent and debateable for all participating parties.

SYNOPSIS

The didactic elements presented here should ease the students’ entry into the working and cognitive processes of design. The essential aspects of these didactic elements include:

- the structuring of the semester plan and the formulation of complex design assignments as a series of interrelated tasks,

- the sensitisation of the potentials and limitations of particular working techniques in the design process,

- the linking of theoretical concepts and the evaluation process

- and the establishment of various communication scenarios with the goal of allowing students to reflect on their own design progress

With the described shift in role assignments, students experience a significant increase in competence and motivation. This also applies to students with little experience and self-confidence in creative process.

The outlined teaching and learning scenarios have been inspired by various theories and discussions in the context of educational workshops and seminars. We believe that there is still much room for experimentation in this area of education. It seems therefore important to us to exchange and share experience and knowledge of design education in a broader context.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

References

– Archer, B L, Whatever Became of Design Methodology, in Cross, N (ed) (1984)

– Bielefeld, B and Khouli, El (2007), Basics Entwurfsidee, Birkhäuser, Basel, CH

– Blowfish Sammlung der Harvard Graduate School of Design, http://www.gsd.harvard.edu/people/students/student_forum/blowf ish.html

– Cross, N (ed) (1984), Developments in Design Methodology, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK

– Curdes, G (1995), Stadtstrukturelles Entwerfen, Dortmunder Vertrieb für Bau- und Planungsliteratur, Stuttgart Berlin Köln, GER

– De Jong, Taeke and Van der Voordt, Theo (ed) (2002), Ways to Study and Reasearch Urban, Architectural and Technical Design, Delft University Press, Delft, NL

– Ehrlich, C (1999), Die Konstruktion der Idee und Ihre Werkzeuge, Wolkenkuckucksheim – Internationale Zeitschrift für Theorie und Wissenschaft der Architektur, 4. Jg. Heft 1, Entwerfen – Kreativität und Materialisation, www.tu- cottbus.de/BTU/Fak2/TheoArch/wolke/deu/Themen/991/ Ehrlich/ehrlich.html, GER

– Gänshirt, C (2007), Werkzeuge für Ideen, Birkhäuser, Basel, CH

– Gänshirt, C (1999), Sechs Werkzeuge des Entwerfens, Wolkenkuckucksheim – Internationale Zeitschrift für Theorie und Wissenschaft der Architektur, 4. Jg. Heft 1, Entwerfen – Kreativität und Materialisation, www.tu- cottbus.de/BTU/Fak2/TheoArch/wolke/deu/Themen/991/Gaenshir t/gaenshirt.html, GER

– Hertzberger, H, Creating Space of Thought, in De Jong, Taeke and Van der Voordt, Theo (ed) (2002)

– Kuhlmann, D (2006), La Cité des Dames, Wolkenkuckucksheim – Internationale Zeitschrift für Theorie und Wissenschaft der Architektur, 10. Jg., Heft 1, From Outer Space: Architekturtheorie außerhalb der Disziplin (Teil 1), http://www.tu- cottbus.de/BTU/Fak2/TheoArch/Wolke/deu/Themen/051/Kuhlma nn/kuhlmann.htm, GER

– Lawson, B (2003), How Designers think – The Design Process Demystified, Architectural Press, Oxford, UK

– Meyer, H (ed) (2003), Palmboom & van den Bout – Transformaties van het verstedelijkt landschap – Het werk van Palmboom & van den Bout, SUN, Amsterdam, NL

– Palmboom, F, Urban Design: Game and Free Play versus Aversion and Necessity, in Meyer, H (ed) (2003)

– Reinborn, D and Koch, M (1992), Entwurfstraining im Städtebau, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart Berlin Köln, GER

– Rittel, HW (1992), Planen, Entwerfen, Design: Ausgewählte Schriften zu Theorie und Methodik, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Berlin, Köln, GER

– Webler, WD (1991), Kriterien für gute akademische Lehre, Das Hochschulwesen No 6 pp 243-249, GER

非常好的教学方法。但如果在中国实施,会有一点点不同。

中国学生的思维和学习习惯和西方人很不相同,有很多类似的改革,当初“看上去很美”,最终却被证明失败。

中国学生实际上很不习惯讨论,协商————因此他们也往往被动地参与这类活动,从而收获甚少。

我曾经尝试过无数的设计教学方法,最后发现最有效率的竟然是——案例教学法!

有点小郁闷。

很同意你的观点。

不少人都把园林复杂化神秘化,其实说白了就是多看多抄多改进,哪有那么多奇怪的理论呢。。

而且在现代中国,能把树种好,就成功了一大半了,别的都是浮云。

设计教育也需要理论,有成功经验应该借鉴学习,消化应用。

的有道理,但是事实上就正像王欣同学说。这个问题大家可以研究一下~还是挺有意义的~

……