by Lars Hopstock

Abstract

With several hundreds of projects designed at different scales between 1926 and around 1970 and as an influential teacher Hermann Mattern ranks amongst the principal representatives of twentieth-century landscape architecture in Germany. The information presented here was collected as part of an ongoing dissertation project about Mattern, which aims at contributing to a better understanding of modernist currents in twentieth-century German landscape architecture. At the occasion of a doctoral seminar about ‘design knowledge’ a new topic was introduced into the author’s research, as Mattern’s notion of design thinking was explored. Despite being considered a progressive, Mattern has mainly been regarded as an intuitively working artist. In the following paragraphs, the wide-spread notion of his work as purely artistic and “untheorised” is put into question. Presented here is a collection of thoughts rather than a finalised argument. The classical scientific notion of theory is rejected in favour of a more inclusive one, which considers his artefacts together with his written thoughts as attestation of his knowledge and theory.

Introduction

The famous style discussion in German garden design around 1900, that led to a reform of garden design, resulted in the development of a geometrical style, the so-called ‘architectonic garden’. This prevailed until the end of the nineteen-twenties, when the idea became popular to take inspiration from the new science of phytosociology and to give expression to more naturalist form. Mattern is seen as one of the important innovators in garden design around 1930. Often his promotion of organic connection between house, garden and landscape is misunderstood as a rejection of the geometric. Instead, all his life he was never dogmatic in questions of form. Mattern occupied himself with the search for design solutions that responded as much to the local conditions as to the changed ways of living. What was needed at that time was not a new style, but a new design approach more in tune with the reality of the new urban society, its social structure, and its technological standard. A sentence from an article he wrote in 1933 together with his first wife Herta Hammerbacher (1900–1985) states: ‘[…] it is not important if a garden is arranged in the so-called architectonic or in the organic style. Crucial is […], if lines […] were deliberately drawn or not’. This sentence encapsulates the essence of his design approach, expressing his rejection of formalisms and his functionalist outlook. However, he thought of himself as an artist and was not interested in mere rationalist problem-solving. Another quote hints at Mattern’s holistic notion of design of gardens:

‘[…] apart from the practical, useful, the applied motivations, which concern visual shielding, commodity, maintainability, independence of weather, and stability, […] also purposeless considerations lead to spatial compositions’.

Figure 01: Portrait Hermann Mattern, c. 1962. Photo by Beate zur Nedden (beatefoto), taken from: Akademie der Künste (ed.), Hermann Mattern 1902–1971, Gärten, Gartenlandschaften, Häuser (1983) p. 4.

Garden shows: the task of inventing

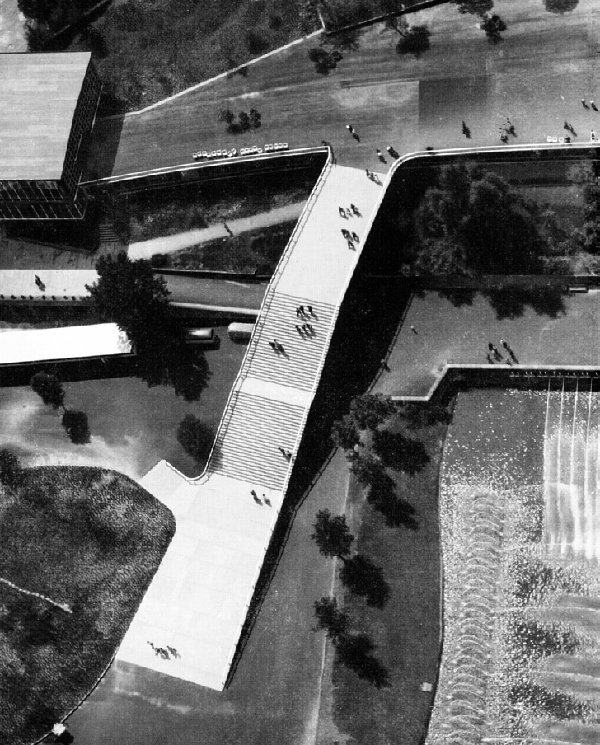

One of the characteristic and designerly aspects of Mattern’s work was his experimental way of dealing with restrictions. After some years of working together with his first wife Herta Hammerbacher and the famous horticulturist Karl Foerster (1874–1970), the first major public project identified with Mattern alone was the Reich Garden Show 1939 at the Killesberg Mountain in Stuttgart, a landmark project for nineteen-thirties landscape architecture (see figure 02). By some conservative and völkisch (racist) garden architects the design was severely criticised as ‘un-German’. One colleague saw in it a modernist individualism that he believed National Socialism should have swept away. Mattern managed to realise an essentially progressive design, despite the unofficial stylistic (Blood-and-Soil) building standards that limited his freedom of expression. When he was commissioned to reconstruct the partly destroyed project after the war in 1950, together with the architect Rolf Gutbrod (1910–1999) he reduced the rustic aspects and turned the Killesberg Park into an airy garden full of strikingly modern features (see figure 03 + 04). Like for the Garden Show in Kassel five years later, he designed transparent, lightweight screens and pergolas to structure the space (see figure 05).

Figure 02: The Reich Garden Show 1939 was built in an exhausted sandstone quarry. View into the ‘Valley of the Roses’. Photo by A. Ohler, taken from: Erich Schlenker (ed.), Das Erlebnis einer Landschaft. Ein Bildbericht von der Reichsgartenschau Stuttgart 1939 (1939), p. 62.

Figure 03: View from the viewing tower over the series of artificial lakes in 1950, originally designed by Mattern for the Reich Garden show 1939. Taken from: Das ABC der Werkakademie Kassel, ed. by. Werkakademie Kassel, Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung (Kassel 1951), p. 12.

Figure 04: Stairs designed by Mattern as the main access to the German Garden Show at Stuttgart 1950. Taken from: H. Mattern, Gärten und Gartenlandschaften (Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje, 1960) p. 135.

Figure 05: Federal Garden Show at Kassel 1955: irregular pergola and spoon-shaped plant containers made from Eternit, designed by Mattern (taken from: Baukunst und Werkform, vol. 8, no. 7, 1955).

For the show in 1939 the planning phase had been more than two years. This second design in 1950 had to be completed within a few months. It represented Mattern’s typical experimental attitude and his effortless use of inexpensive materials. The budget was extremely tight, but to make the most out of little was something that provoked Mattern’s creativity. He was respected as a ‘tinkerer’. In a revealing interview not long after his death, his second wife Beate zur Nedden spoke about Mattern’s passion for financially limited tasks: ‘Since garden exhibitions have become highly remunerated institutions, into which are built amounts of several millions, he was put off them […]. He was a man of improvisation […].’ This meant that obstacles were an asset to him rather than a hindrance. Limitations seemed to trigger his creativity and make it easier for him to break with conventions.

Mattern was also seen as a provocateur. In congruence with the early modern movement he completely broke with the traditional canon of garden art. Traditional form he wanted to leave behind, his art was ‘the art of invention’. A vivid example to illustrate Mattern’s search for the new was the Federal Garden Show at Kassel 1955, which—like his design for the Reich Garden Show 1939—received mixed reviews. One faction praised Mattern for taking risks, for experimenting with both new constructions and a new formal language and making a truly avant-garde statement against restorative tendencies. The other faction rejected all this, calling the experimental design for planting containers, handrails and other details mere gimmickry for the sake of being new. Mattern even emphasised the damage to the stairs in front of the orangery castle to give the impression that his new shapes symbolically take over the historical forms (see figure 06). The ruined castle itself he repaired with transparent new steel-and-glass architecture. It may not seem very special to an architect today, but in landscape architecture so soon after the war such an experimental attitude for some people was quite shocking.

Figure 06: Amoeba-shaped plant beds floating over the stairs in from of the reapired ruin of the old orangerie. Photo by Beate zur Nedden (beatefoto), taken from: Akademie der Künste (ed.), Hermann Mattern 1902–1971, Gärten, Gartenlandschaften, Häuser (1983) p. 81.

More than knowledge and skills: teaching design expertise in landscape architecture

In 1966 Mattern prompted the Senate of Berlin to establish an annual design competition for young landscape architects called ‘Peter-Josep-Lenné Prize’, which is still regularly held today. Together with the prize giving ceremony Mattern organised a spectacular exhibition of the work of Peter Joseph Lenné (1789–1866), the Royal Prussian Director General of Gardens. At the occasion of the exhibition opening and the award ceremony Mattern gave a speech, in which he drew on the writings of two influential European garden theoreticians, Humphry Repton (1752–1818) and Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld (1742–1792). He quoted Repton’s demand for a better education of garden designers and Hirschfeld’s demand for an acceptance of garden art into the Academies of Fine Art. At the Kassel Werkakademie, Mattern himself in 1949 had established a teaching course where for the first time in Germany landscape architecture stood side by side on one level with the other arts. Although in Kassel the teaching was not purely artistic, the design focus was stronger than in other existing courses. At the mentioned exhibition opening Mattern also expressed some thoughts about the professional profiles of architects and engineers, which further illuminate his notion of design as professional occupation:

An engineer should be far more […] than […] someone who occupies himself with precast or still to be formed materials. Because engineer comprises ‘ingenium’, the genius, that is the essence of the humanities [Geisteswissenschaften] themselves, namely in its application to the matter that surrounds us.

Mattern’s mentioning of the very ‘essence of humanities’ that is comprised in the word ‘engineer’ (the official academic title for landscape architects and architects in Germany) hints at his notion of something beyond the technical, the scientific, and even the artistic—something more than the sum of all this. Admittedly, this sounds rather vague, so to understand more about Mattern’s notion of designerly knowledge it might be useful to take a look at his concepts for the education of landscape architects.

When in 1950 the professional journal Garten und Landschaft asked four landscape architecture professors about their concept for teaching, Mattern revealed some of his personal views on this topic. In his overall teaching concepts he clearly differentiated between scientific and designerly talent. For the idea to teach landscape architects at an art academy he had two main arguments. Firstly, akin to the concept for the Bauhaus school, to become a good designer Mattern believed a student should get the possibility to concentrate on designing in exchange with other designing disciplines:

Principally we have to avoid right from the outset to educate semi-scientists. Whole scientists have to make their way via the universities. But it is also fruitless and inefficient to develop half measures on the field of the designing disciplines. True design talent can only be fostered at corresponding institutions, which exclusively occupy themselves with questions of design.

Mattern’s second core argument was that he considered certificates useless. This was why he saw it as an advantage that, in contrast to a German university, an art college was allowed to select suitable candidates through an entrance examination instead of looking at certificate grades. In accord with his standing point the Werkakademie did indeed not issue graded certificates, just confirmations of attendance for the seminars and studios. Mattern complained about the naivety of many graduates who thought the degree certificate made them a good designer. Usually they were shocked when in the professional world nobody was interested in certificate marks but only in their skills and experiences.

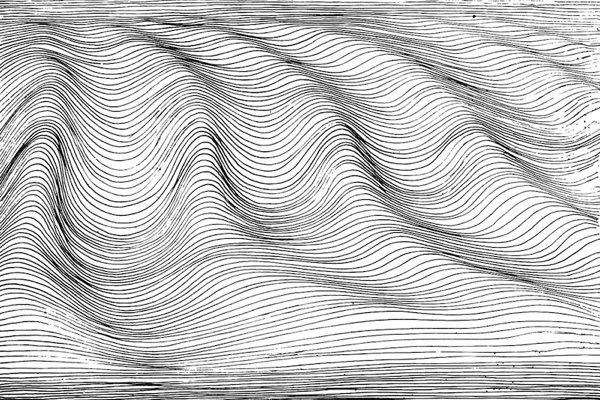

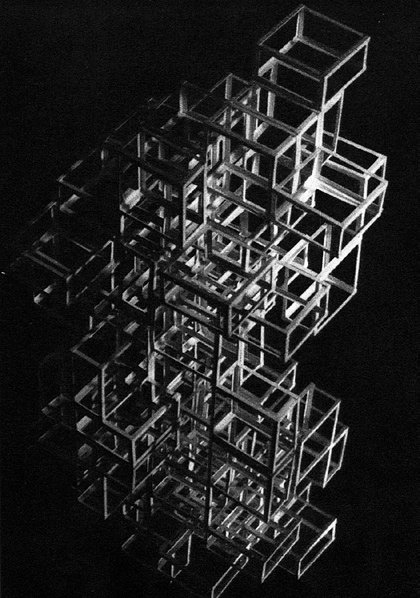

In 1961 Mattern finally answered a call onto the Chair of Garden and Landscape Design at the Berlin Technische Universität. Here he hoped to gain the authority to further increase the awareness for the profession and for the grave situation regarding landscape consumption and bad planning practice. He considerably widened the curriculum of the course and also introduced creative exercises who recall the famous foundation courses the Bauhaus offered during the 1920s (see ill. 07 + 08). Mattern still believed that the initial teaching of design skills was a precondition for becoming a good landscape architect:

As experience teaches, it comes more naturally to students coming from the high schools to pass over into purely scientific studies than to take up a technical or artistic, respectively creative education. To impart to the students the essentials […] they are initially—beside the elementary scientific subjects—prompted to take measure, to recognise scale, to observe and to perceive through graphical and sculptural exercises.

Figure 07: Original English captions: ‘Exercise: the line. Drawing of a line whose movement is taken up and increased towards the middle’ (H. Mattern, ‘Der Studiengang für Architekten des Landschaftsbaues, der Gartenkunst und Ortsplanung an der Technischen Universität Berlin’, Garten und Landschaft, 9, 1963, 282).

Figure 08: Original English captions: ‘Exercise: plastic and constructive shaping. A flexible cardboard strip becomes firm through folding at right angles. Addition: to make a frame; frames to form a structure; structures to form a three-dimensional (spatial) creation’ (H. Mattern, ‘Der Studiengang für Architekten des Landschaftsbaues, der Gartenkunst und Ortsplanung an der Technischen Universität Berlin’, Garten und Landschaft, 9, 1963, 283).

One important reason for Mattern’s exit from the university in 1970—beside a serious illness—was the changing attitude of the younger generation at the university. By the end of the 1960s students were highly politicised and wanted to discuss basic questions of social coexistence. Mattern got disillusioned by all the talking; to arrive at solutions he expected his students to draw. Despite his critical distance to one-dimensional rationalism, he was more and more seen as an old-fashioned modernist. This perception of his works only really started to change at the end of the 1980s, when a general recollection of the profession’s modern heritage began. Mattern distrusted the normative character of classical or rationalist design rules as well as the reductionist mainstream of the scientific academic world. For example, regarding his concept for landscape planning he expressed doubts that a standard guideline be useful. In his opinion, because central European landscape was so thoroughly influenced by humans it was constantly changing and the planning process should not be standardised but remain flexible. At the same time he was strongly connected to the social aims of the modernist project. Considering this conflict, he can be called a very critical modernist.

Conclusion (an attempt)

Mattern’s position was not the mainstream, nonetheless his influence in Germany was considerable. His works are today regarded representative of the younger history of landscape architecture, and his thinking, while often considered untheorised, has come to be acknowledged as an essential part of the twentieth-century intellectual legacy of our profession. By introducing some typical aspects of his design practice and thinking it has been tried to show how an experienced professional saw designerly expertise as a specific type of knowledge. Mattern himself in teaching regarded design knowledge as different from scientific knowledge. The high importance he attributed to the training of this knowledge is expressed by his introduction of foundation courses for the training of design skills. In the limited space provided, it has been tried to contrast aspects of Mattern’s own designerly expertise with some of his personal notions of designing. One main point was to show that the awareness of the specific characteristics of designerly thinking is something natural in a design profession like landscape architecture, and that it has long been part of the academic curriculum. Experiment and improvisation were both part of Mattern’s practice as a designer and of his teaching as a professor. Moreover, those characteristics that are today discussed as designerly characteristics, like the preference for improvisation and non-linear processes, were intrinsic parts of Mattern’s personality. This raises other questions after the role of natural talent for creativity.

After the extensive efforts during the 1960s to find a scientific formula for the design process, there is a broad consent that it cannot be explained by a clear-cut model. Thus the way designers actually work somehow escapes the positivist tradition we usually connect with the first half of the twentieth century. So if we consider historical value of the analysis of Mattern’s thinking, it reveals a lot about the complexity of modernism. His way of dealing with political, material and other impediments and limitations in his projects reveals an expertise that may contribute to today’s discussion about both research about, and research through design.

>> 点击这里查看本文中文版《论现代主义风景园林师赫尔曼·马特恩(1902—1971)的设计师式思维》