如今,城市几乎在一夜之间形成。全球的城市人口数量急速上升,贫富差距也在不断增加。企业家、名人和体育新星不断出现,他们是社会上耀眼的群体,然而同为当今社会产物的流浪者却是悄无声息、不为人见的一个群体。这一现象已经在全球很多主要城市出现,我们悉尼的“后院”也不例外——这里每天都在上演着有关人类的悲剧,绝望与无助的故事。我们当中的大多数人并没有看到这些,或者不愿看到这些,因为每人都得为生计奔波。

尽管社会上有人确实真正关心无家可归者,但也有人对此充满了恐惧和偏执。悉尼市政府在推进一项两处流浪者经常光顾的小型城市公园的重建计划时,就引起了公众的些许不安。这两个公园分别是位于悉尼中央商务区边缘的瓦拉穆拉公园和帕克街公园。瓦拉穆拉公园又称为“流浪汉公园”,是20世纪70年代因修建高架铁路线而拆除一排房屋遗留下来的一片公共区域。它被险恶的高铁横穿而过,又毗邻一处流浪者招待所,于是便成了流浪汉长期居住或者短期住宿的场所。这里不久便因为毒品交易和酗酒而臭名远扬,公园的环境和设施更是受到严重破坏,卫生程度也远远低于可接受的社区卫生标准。这种负面形象甚至改变了路人的行为习惯——他们宁可专程绕远路也不愿意穿越该场地走捷径。

大多数人都认为流浪汉公园将继续保留其被流浪者所使用的主要用途。对于市政府来说这是一个难题,因为他们不希望让广大公众认为政府提供设施来合法化并鼓励长期的流浪。如果必须要达到一个平衡——本质上来说,不是要通过设计将流浪者们排除在公园之外,而是要通过设计将更广阔的社区融入到这个公园里来,才能鼓励公园的共享使用和公共所有权。

我们从一块人工地形,联想到澳大利亚郊区住所平均尺寸的房间,从而提出流浪汉公园最初的改造概念。这一创意受到了一些人的赞赏,同时也让人感到害怕——每一堵“墙”都可能隐藏不能被社会所容忍的行为。随着时间的推移,公众和政府中的偏执狂削弱了我们大部分的最初概念,同时公众安全问题也几乎是一个困扰。在设计这样一个公共空间时,还要考虑现有的法律和规范,这可能会为我们的设计带来一些困难。

在流浪汉公园的最终方案中,我们试图保留一个舒适的人性尺度,并配备精心摆设的座椅,以在这个大公园区域中营造小尺度空间。这些座位的设计是我们对公园使用者的行为进行观察后创作出来的——他们往往喜欢组成小群体,在公园里的不同区域聚集。这一行为特征体现在桌子四周座椅的朝向,同时座椅舒适的宽度也让人们能够朝另一个方向坐下。这种类似于“回旋飞镖”般的座位形式,在为更多的人提供聚会餐饮的同时,也能为每个个体保留一定的空间。此外,座位还必须体现清洗过程,从而为维修机械留出通道。

作为一个以硬质景观为主的城市环境,流浪汉公园交替采用新的可再生混凝土以及用于分隔的混凝土条进行铺装,并与公园的空间相呼应。由于有关部门担心雨水坑会被用于藏匿非法毒品和用具,现已将其淘汰。于是混凝土条不但可以帮助调解铺装方向变化,同时还能起到雨水坑的作用——疏导雨水和压力清洗的地表径流。

新的公园为公众提供了以现有的木麻黄树为檐篷下的一片片草坪,还有新种植的成年马氏射叶棕榈树丛(荷威椰子)和开花的攀援植物。当这些植物成熟时,邻近那家流浪汉招待所的方格篱笆,就会逐渐变成一堵绿色的墙壁,而新的厕所将会拥有一个植物层层叠叠的绿色屋顶。夜晚,由于人们对集中照明的要求,使得厕所的位置更加突出——它成为公园的“灯笼”,且在白色马赛克墙的衬托下更为耀眼,以阻止涂鸦行为。厕所那带图案的门是经过特别定制设计的,它们通常都有一条小缝,以便进行监察工作。

自2011年3月流浪汉公园开园以来,其社会环境出现了一些明显的变化。公园在社区中不再背负让绝大多数人都预感耻辱的名声了——许多人之前不敢冒险穿过公园,现在都能非常自由地进入和穿越其间了。尽管流浪者们在很大程度上可能还在占用着公园并将它当作是夜晚的临时住宿,但它着实加强了社区的融合。公园的使用者们也反馈了积极的评价,甚至还有人说这里就缺一个烧烤区了。我们认为,对于改造像流浪汉公园这样的场所,并不是要和无家可归产生的根源或是毒品酒精的滥用的痛苦事实作斗争,而是通过精心设计来维护共享的城市空间,以缓解紧张局势,提高社会对那些不幸人群的宽容和接纳。我们希望,流浪汉公园在一定程度上改善那些无家可归的人们的生活的同时,增加社区对于这个无声人群的接纳。

项目位置:悉尼市乌鲁姆鲁

建设单位:悉尼市政府

景观设计:Terragram事务所

建筑设计:克里斯 艾略特建筑师事务所

施工单位:汉森 云肯

设计及施工时间:2008年至2011年3月

撰文:Terragram事务所

翻译:王田媛

图片来源:Terragram事务所

As cities today appear virtually overnight and urban populations soar across the globe, there exists an ever increasing gap between the rich and poor. While societies flaunt the entrepreneurs, celebrities and sport stars they produce, the homeless – also products of society, are voiceless and invisible. As is the case in many of the world’s major cities, our ‘backyard’ of Sydney is no different – stories of human tragedy, hopelessness and desperation are played out each day. Most of us do not see it – or do not want to see it – as we go about our daily lives.

While genuine concern for the homeless does exist, there is also a fear and paranoia amongst society. It was with some trepidation that the City of Sydney Council stepped forth with plans to renew two small urban parks frequented by homeless people – Walla Mulla Park and Bourke Street Park, on the fringe of Sydney’s CBD. Walla Mulla Park, commonly referred to as the ‘homeless man park’, is a fragment of public space left over from the demolition of terrace housing, due to the construction of an overhead railway line in the seventies. The park, dissected by the ominous viaduct, and neighboring a homeless men’s hostel, was reclaimed by a number of homeless people, some long-term residents and other transient dwellers. The site rapidly gained a reputation as a notorious location for drug and alcohol abuse and dealing, high levels of vandalism and general uncleanness far below acceptable community standards. This negative image changed the behavior of passers-by – instead of taking short-cuts through the site, people would detour to specifically avoid it.

The brief for Walla Mulla Park realistically acknowledged that the park would continue to retain its predominant usage by the homeless. It was a conundrum for the council, as they did not want to be seen by the wide public, as legitimizing and encouraging chronic homelessness by providing amenities. A balance had to be achieved – essentially, not designing the homeless out of the park, but rather designing the wider community into the park, thus encouraging a shared use and ownership of the site.

Our original concept for Walla Mulla Park, was based on an artificial topography evoking the idea of average sized rooms in the Australian suburban house. This idea, while appreciated by some, also terrified others-every ‘wall’ could hide behavior not condoned by society. With time, the paranoia of the public and council diluted many of our initial ideas, with public safety almost an obsession. It is difficult to even contemplate the number of regulations and constraints that exist, when designing such a public space.

Our final plan for Walla Mulla Park, attempted to retain a comfortable, human scale, with seating deliberately configured to create smaller pockets of space, within the larger park area. Design of seating, responded to an observation of the behaviour of residents in the park, as they tended to create small groups, gathering in different parts of the site. This is reflected by orienting seats around tables, but due to their width enabling people to sit the other way as well. The ‘boomerang’ like forms of the seating while catering for larger gatherings of people, also allow individuals to maintain their personal space. In addition, seating also had to reflect cleaning procedures, creating trafficable corridors for maintenance machinery.

As a predominantly hardscaped urban environment, the ground surface of Walla Mulla Park is characteristic to the space, with an interplay of new and recycled concrete pavers, and dividing concrete strips. The strips at times serve to mediate change of direction in paving, while also helping to direct run off of rain water and pressure cleaning, in the absence of any stormwater pits (which were eliminated for fear of hideout places for illicit drugs and utensils).

Areas of lawn under canopies of existing casuarina trees were provided, as well as new planting of clusters of mature Kentia palms (Howea forsteriana) and flowering climbers. While plants have not yet had a chance to mature, the trellis against the wall of the neighboring hostel, will gradually be transformed into a green wall, and cascading green roof to the new toilet block. At night, the requirement for intensive lighting emphasizes the toilet to such a degree, that it becomes a ‘lantern’ to the park, further highlighted by white ‘mosaic’ walls of tile fragments, to discourage graffiti. The toilet’s custom-design patterned doors are usually left ajar to facilitate surveillance.

In the few months that have passed since the opening of Walla Mulla Park in March 2011, there has been a perceptible difference in the social environment. The park no longer carries such an overwhelmingly foreboding stigma in the community – many people who would not have dared venture through the park previously, now enter and pass through quite freely. Although the homeless might largely occupy the park, and use it as a make-shift home for the night, there is an enhanced mixing of the community. Feedback from park residents has also been positive, one of the residents saying that the only thing missing was a barbecue. We accept that the renewal of a park such as Walla Mulla Park, does not combat the root of homelessness, or the bitter truths of drug and alcohol abuse. Yet we continue to believe that well designed and maintained shared urban spaces can reduce tension and increase tolerance and acceptance of less fortunate members of our society. Hopefully Walla Mulla Park, to some degree, will improve the lives of those who find themselves without house-keys, and at the same time increase community acceptance of a voiceless population.

Location: Woolloomooloo, Sydney

Client: City of Sydney Council

Landscape Architect: Terragram Pty Ltd

Architect: Chris Elliott Architects

Builder: Hansen Yuncken

Time Period: 2008-March 2011

Text : Terragram Pty Ltd

Translation: WANG Tian-yuan

Photo Credit : Terragram Pty Ltd

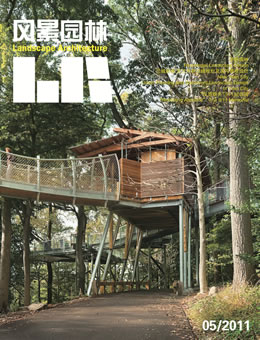

《风景园林》2011第5期导读

《风景园林》2011第5期导读

Leave a Reply